#14: Portfolio Update 6/2021

New entrants to our portfolio; more walled gardens; what happened to disclosing gross billings?

Welcome to Quo Vadis, your periodic source for fresh programmatic news and off-the-beaten-path perspective. Click here to join the conversation.

Promo — If you share Quo Vadis with 5 friends who would also like to get our point of view delivered straight to their inbox, we’ll give you a free Quo Vadis+ subscription for one year. All you have to do is email 5 friends and CC makers@lemonadeprojects.com.

Yesterday was Prince’s birthday — we like to call it Global Prince Day. Just prior to the 2004 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony where Prince crushed a massive guitar solo, Rolling Stone published its list of the Top 100 Guitarists of All Time. Prince was not on it. Then he did this… now we know.

Programmatic Pure-Play Mojo Hits Reality, A Few Show Staying Power

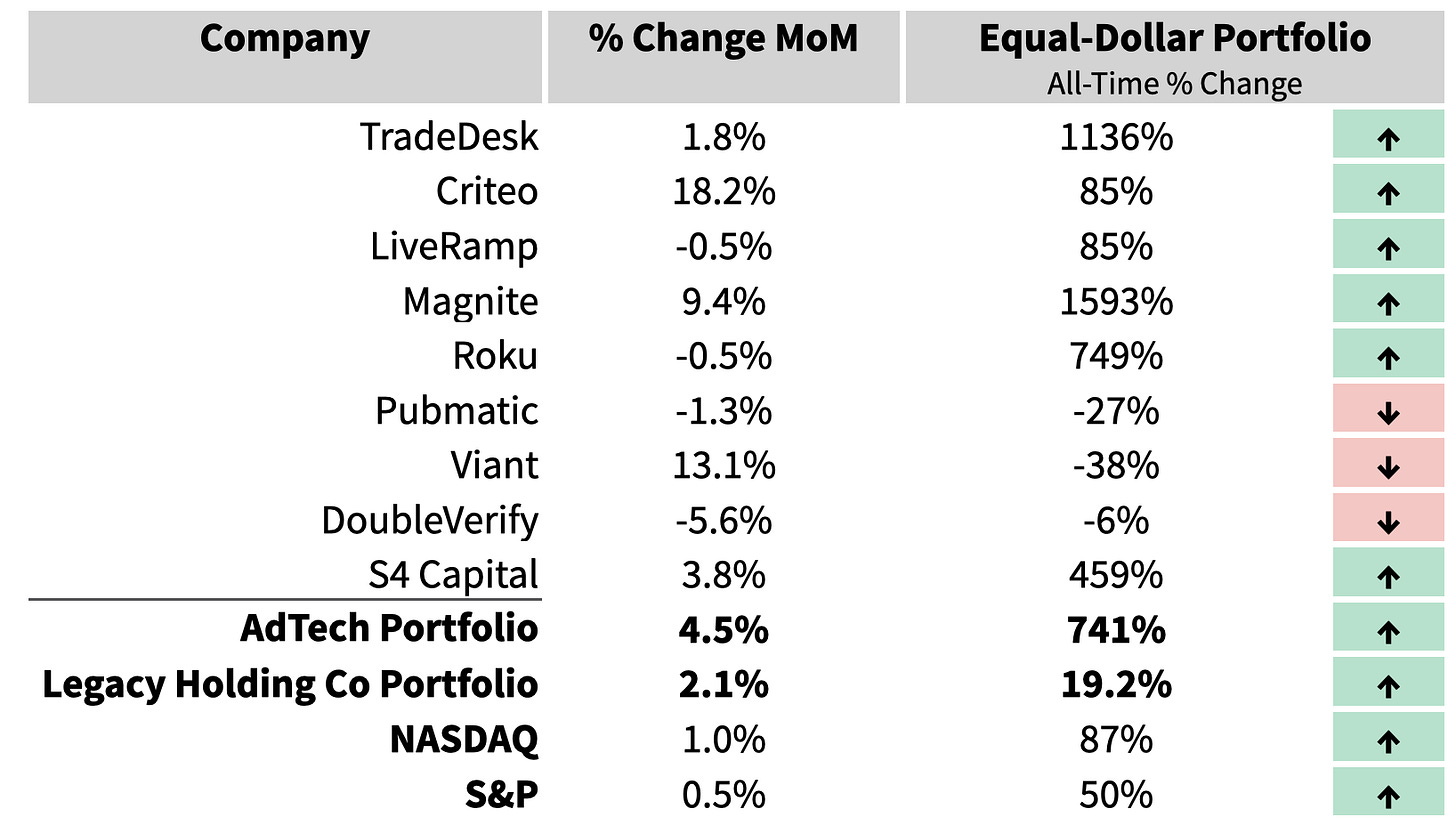

Since our inaugural portfolio launched on March 4, our Quo Vadis basket of programmatic pure-play stocks has hit some bumps in the road, moving downward from 835% in March to 741% as of June 7, 2021.

Reminder: We’re running an equal-dollar portfolio that starts in January 2018 (we explain why here). We include stocks that are either 100% dependent on programmatic advertising or heavily reliant on it.

In other words, had you bet $100 on this basket of stocks in January 2018, you’d have $741 of extra cash in your pocket today, and you would’ve beaten the NASDAQ by more than 8x.

Food For Thought: When the average advertiser puts $100 into open-web programmatic advertising, do you think it gets a 741% return on investment? In a like-for-like cash-on-cash world, wouldn’t any CFO certainly expect programmatic ad investments to outperform our portfolio? If not, the CFO would be better off buying these programmatic stocks, right?

New Entries

Over the past two months, we’ve added two new players to our portfolio:

Viant Technology Inc (NASDAQ: DSP), a managed service DSP that looks like a managed service Rocket Fuel player of yesteryear. We’d love to see Viant’s insertion orders and who on the buy-side is signing off. Wishful thinking!

DoubleVerify Holdings (NYSE: DV), a verification monitoring company. If you were buying bonds instead of impressions, you’d want a quality rating. You’d also want the rating to be reflective of the asset’s underlying value. At least that’s what happens in the non-advertising world. Keep a lookout for companies like DV to getting into universal ad quality ratings. It’s the missing link and the key to breaking sell-side information asymmetry and massive opportunity for advertisers.

Anywho… both stocks are down since their recent IPOs. Worse than that, they’re dragging down our overall portfolio gains.

The Trade Desk (TTD)

TTD is off over 33% since reaching a peak of $901/share in November 2020. The most interesting insight is how TTD no longer seems to be reporting topline gross billings as per its 1Q21 10Q filing. We’ll have to check whether management will report gross on an annual basis next February.

We see three reasons for such an omission:

The Trade Desk is worried about showing margin compression to investors.

Management has found a new post-cookie way to increase take rates, but they don’t want clients to see how much they’re “taking.”

Imagine for a moment that management sees headwinds with topline growth as ad budgets seek new/better alternatives, but they also need to show net revenue growth to investors. What do you do? Increase take rates.

Either way, let’s put another feather in the non-transparency cap of programmatic advertising.

Rule of thumb — For all of our brand-side readers out there, our advice is to ask your DSP about getting log data on clearing price and bid price. Try it… the results are eye-opening whether you succeed or not.

Criteo (CRTO)

Criteo debuted a logo makeover on Friday. What say you? Like it? Don’t like it? Don’t care?

The market seems to like it. The stock was up 10% since and edging closer to its all-time high of $54, last seen in 2015. Quo Vadis gives a big high-five shout-out to CEO Megan Clark and CFO Sarah Glickman for finding a smart turnaround strategy and not deviating from it. Kudos!

Criteo’s Retail Media Will Pay Off

Starting with the first banner served in 1994, it took 27 years for digital (search, social, display ads) to reach 70% of global media spend ($557 billion).

Today, global trade advertising budgets are estimated to be ~$500B+, but only ~5% is digitized. How long will it take for trade budgets to digitize? 27 years? Unlikely. We don’t think anyone should be surprised to see a half-life growth trajectory play out.

Money always catches up to eyeballs

With 20% of retail sales happening online in the US, and 30%+ in other markets like the UK, we’d expect the money to catch up to eyeballs much faster than it did with past forms of search and display ads.

In any case, Criteo’s acquisition of HookLogic in 2016 for $250 million not only looks really savvy, but it’s a safe lifeboat too.

With $537 million in cash, we wonder what Criteo will buy next as the world moves from a few walled gardens to many. This new world of many walled gardens — big, small, and everything size in between — will need intermediaries to facilitate trades between parties in order for advertising to function. Criteo could be well-positioned to play a key role as long as it maintains its massive universe of shopper conversion data. (More on that subject below.)

Viant (DSP)

Let’s cut to the chase. We’re not Viant’s biggest fans. It turns out that investors are not huge fans either. Viant IPO-ed at $51/share just a few months ago, but the stock is already down 38%.

If forced to make a bet, we think there’s a better chance for more downside pressure than upside wins in a market that’s well past its David-Goliath stage.

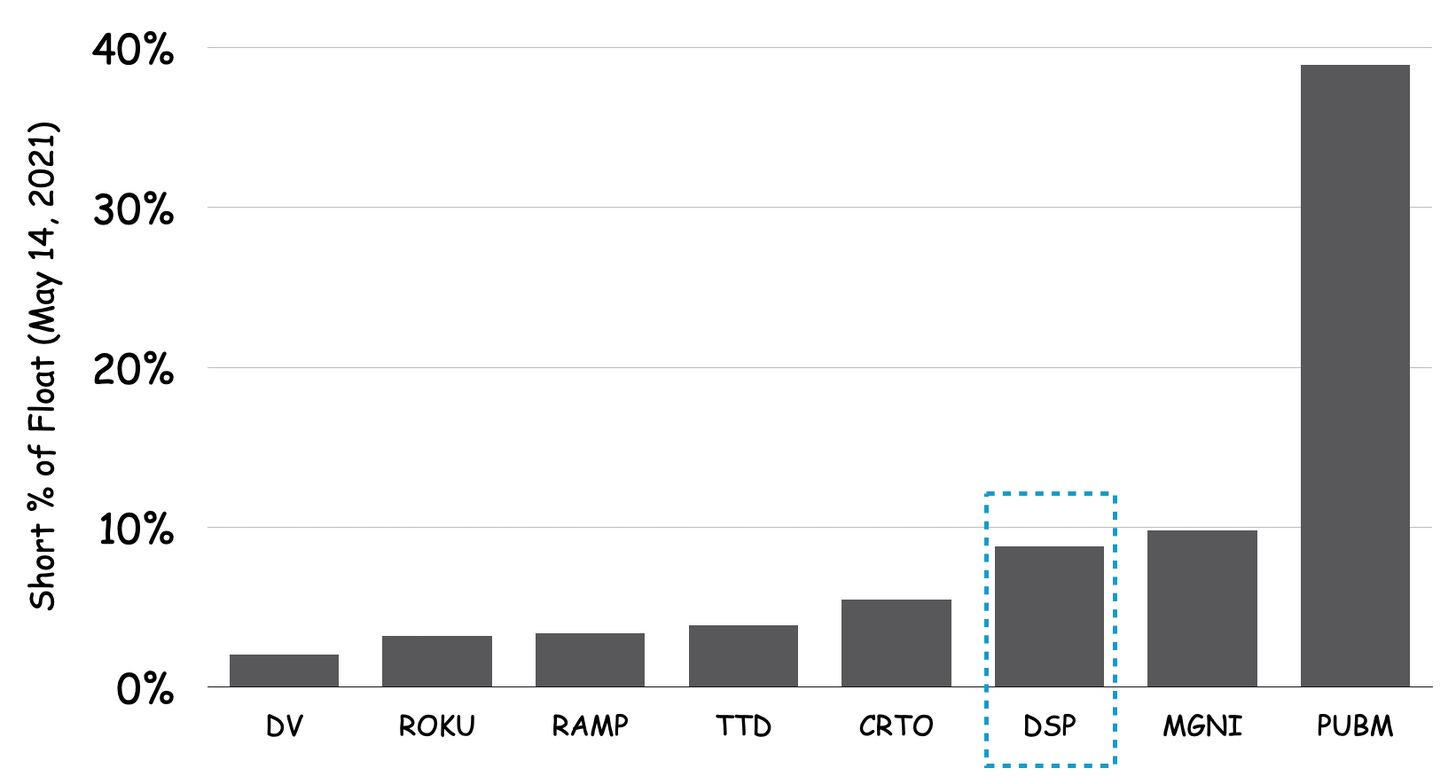

Moreover, with 9% of Viant’s shares shorted, it’s on the higher end of the scale but not even close to Pubmatic — we’ll get to PUBM in a second.

The good news

When we look at the month-over-month percentage change in shorted shares from April to May, it appears that investors are finding a bit more comfort, with 22% fewer shares shorted.

The one thing we do like is the DSP’s 36% ROIC and large economic spread over its cost of capital sitting at 7.5%. That said, Viant’s revenue base is relatively small while net operating profits (NOPAT) is just $21M. In a market full of alternatives, we don’t see Viant being a long-term factor at this time.

Things Change

With $256 million in cash, not much debt, and a decent working capital position, we would not be surprised if management makes an acquisition or two.

Given Viant’s large gross margins (reminiscent of Rocket Fuel), and what appears to be a similar operating model dependent on managed service as a quasi-media agency (humans), management should be investing in productivity tools for line managers and staffers to drive Kaizen (continuous process improvement) and get more output from fewer people.

Managed service models are tough nuts to crack. But if management can figure out how to be 10x better than other managed service competitors, people-based models can be profitable because advertisers always need extra hands.

Magnite (MGNI)

Let’s flip to the supply side. We’ll start with three observations on Magnite:

Magnite announced that Tom Kershaw, the company’s chief technology officer (CTO) for the past four years, will leave to pursue an opportunity outside of adtech.

When it comes to short-sellers, Magnite is in a similar position to Viant (see above), but the month-over-month change in the number of shorted shares is up 15% which is not a great sign.

Similar to The Trade Desk, Magnite stopped reporting gross revenue (ad budget flows) after 2019. Why? The same three explanations as TTD still apply (see above).

All that aside, MGNI is still the biggest contributor to our equal-dollar portfolio, up 15x since January 2018, and contributes 42% to our overall $741 in gains.

Pubmatic (PUBM)

When it comes to investor interest in shorting adtech stocks, Pubmatic is the darling of the ball.

Looking at data from MarketBeat going back to January 15, Pubmatic’s short interest has been on an elevated rollercoaster ride. At one point in mid-February, the percentage of floated shares shorted surpassed 90%.

By mid-March, PUBM’s stock price started falling from a peak of $69 (March 1), while short interest momentarily declined to 40%. But keep in mind, this was still 10x the average short interest of all the other stocks in our programmatic portfolio.

Insider Selling

Simply Wall St. sums up the situation in two recent articles. The first one tells us about big insider selling moves:

“We wouldn't blame PubMatic, Inc. (NASDAQ:PUBM) shareholders if they were a little worried about the fact that Howard Hartenbaum, a company insider, recently netted about US$784k selling shares at an average price of US$29.43. Probably the most concerning element of the whole transaction is that the disposal amounted to 67% of their entire holding.”

The second article (published 13 days ago) provides a thorough DCF with totally rational assumptions indicating the $24 fair value of Pubmatic stock. PUBM was trading at $34 on May 26 and is already down to $29 as of June 8 (and likely falling more).

For all our MBA readers out there, Pubmatic’s situation is a real-life case study in strategy, finance, operations, economics, and game theory. Even though PUBM’s growth situation looks a bit dire, management is generating a relatively large economic spread between ROIC and cost of capital of 26%, albeit on a small operating profit base of just $26 million.

If we only knew something about Pubmatic’s unit economics

On June 2, Exec Edge sat down with PUBM’s CEO, Rajeev Goel, to find out more about the company and how digital advertising is transforming the industry. The opening paragraph gets into the most important factor for all open-web programmatic players — marginal cost management:

“To succeed in digital advertising, a company must excel in processing speed and the quantity of data it can process efficiently. PubMatic, Inc. (Nasdaq: PUBM) is able to generate better outcomes by owning its own infrastructure, which allows it to be more transparent with its customers and innovate at a more rapid pace.”

First, let’s take the word “transparent” with a giant grain of salt. If PUBM (or another pure-play programmatic outfit other than Criteo) wanted to be transparent, they would report audited gross billings to let investors know their ability to attract ad budgets, and they’d also provide quarterly information on unit economics (e.g., impressions transacted).

Secondly, let’s dig into the importance of “processing speed,” “quantity of data,” and “better outcomes.” What Mr. Goel is really saying is that Pubmatic needs to maximize the volume of impressions transacted (unit economics) going through its data center clusters in order to minimize its marginal cost below the price it charges publishers (take rate) in order to make and grow reasonable economic profits.

Given the short-selling interest and insider selling, there appears to be very little confidence in such an outcome occurring over the foreseeable horizon. And let’s not forget the backdrop of competing SSPs, who are in a better position to find and sustain economies of scale.

The Rub: When programmatic players are pressured to prioritize ad budget flows, they have to sacrifice the ad quality (supply) they let through their auction pipes. If buyers are unaware of this dynamic, and if sellers don’t reveal it or successfully put lipstick on a pig, then buyers will find themselves a classic lemon market.

LiveRamp (RAMP)

No doubt, LiveRamp is the eye of the data storm. From our viewpoint, RAMP is holding up well given the amount of uncertainty around how data will be used (or not) as the lubricant in the programmatic machinery.

Within our equal-dollar portfolio, LiveRamp is doing its part and modestly contributing to the upside. But what we — and investors — are most interested in is RAMP’s road to profitability.

Getting Profitable

Let’s take a back-of-the-envelope look at LiveRamp’s unit economics:

Top-line Revenue growth is slowing, but RAMP is getting more out of each customer (see avg. revenue/customer below).

Sales Performance is more than respectable as customers look for data tools in an advertising space that is rapidly moving toward a multi-walled garden world. We see LiveRamp — and competitors — as the arbitrators of Ricardian trades between walled gardens (e.g., Safe Haven).

Variable Cost is the key gotcha in adtech. It appears that LiveRamp is focused on squeezing more productivity out of past investments in infrastructure to reach profitability.

Although LiveRamp added ~50 more heads between 2020/2021, they put the brakes on Fixed-Cost growth (SG&A)

Given variable and fixed-cost controls, Total Cost has flattened. We expect management to keep a lean, flat-line approach over the coming years.

That leaves us with Average Revenue/Customer/Month, which is growing at a nice clip.

Profit is moving in the right direction, but the question is, when will RAMP reach profitability?

Pricing, Marginal Cost Analysis, and Profitability

If we run a simple regression of Total Cost against Direct Customers (the only decent proxy available for unit economic analysis), we can get a directional idea of profitability.

Marginal Cost per Direct Customer = $58K/month. In other words, every time LiveRamp’s sales team adds a new customer, the company incurs a $58K cost (the slope of the regression line).

If we swap out Total Cost, replace it with Revenue, and run a simplified regression model, we can “see” Marginal Revenue, which is just a fancy way of saying price. In LiveRamp’s case, they price services at $40K/month per customer.

With a $40K/month price tag and $58K in cost, the Contribution Margin per customer is –$18K.

If LiveRamp can manage to keep reinventing and use some of its $580 million in cash to invest well in the post-cookie world, manage cost, grow Direct Customer counts by 40 to 50 per year, and most importantly, squeeze 5-10% growth out of existing customers, then profitability could be reached between 2026 and 2028.

Playing into a Major Macro Trend

While everyone in advertising has gotten used to a few big “walled gardens,” perhaps the biggest macro trend on the horizon is a world of many walled gardens.

Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix, and Google are the big players today, but many more are forming.

Streaming+ services growing like weeds, they all walled off first-party data.

The same goes for Retail Media players — Walmart, Target, and Instacart in the US and similar companies in other major markets.

Big publishers are locking down data, plus publisher consortium players like Ozone in the UK and WeMass in Spain are aiming in the same direction.

Large advertisers are also aiming to capture more first-party data and lock it down. And who knows, as ad money flows toward more predictable direct response strategies, it’s not unfathomable to see CFOs book data as a balance sheet asset and also write off depreciation expenses.

Data "integrators" like LiveRamp, Neustar, Infosum, ID5, and more are all selling tech to either make data walls and/or facilitate trading between them in order for advertising to function (e.g. LiveRamp’s SafeHaven and other “clean room” mechanisms)

Rule of thumb: If you read Brad Burnham’s 2007 piece Google’s Data Asset, you’ll see exactly why everyone wants to lock down data and become a walled garden. It’s all about data having an abnormal characteristic called increasing marginal returns. More data trades equal more marginal returns. When various walled gardens trade with each other concepts like Metcalfe’s Law come into play.

Econ Geekout Time

What's super interesting to Quo Vadis is how the Ricardian concepts of comparative and competitive advantage of data production might play out in the form of “trade” agreements that can make each walled garden better off.

English economist David Ricardo thought of this way back in 1817 in "Principles of Political Economy and Taxation." Ricardo argued that the notion of comparative advantage (e.g., a walled garden’s ability to produce data at a lower opportunity cost than another walled garden trading partner) makes both parties better if they can somehow make a trade.

Futurist Moment

Imagine the CFO of ACME Co, a major advertiser that has gathered tons of first-party data and locked it down. The more good trading partners ACME can find via cleanroom trades, the more its data is worth. With such a mechanism at her disposal, the CFO can “mark-to-market” ACME’s data value on the balance sheet as an operating asset.

Ask Us Anything (About Programmatic)

If you are confused about something, a bunch of other folks are probably confused about the same exact thing. So here’s a no-judgment way to learn more about the programmatic ad world. Ask us anything about the wide world of programmatic, and we’ll select a few questions to answer in our next newsletter.

Join Our Growing Quo Vadis Community

Was this email forwarded to you? Sign up for our monthly newsletter here.

Get Quo Vadis+

When you join our paid subscription, you get at least one new tool every month that will help you make better decisions about programmatic ad strategy.

Off-the-beaten-path models and analysis of publicly traded programmatic companies.

Frameworks to disentangle supply chain cost into radical transparency.

Practical campaign use cases for rapid testing and learning.

Great analysis, TT. And I agree ... Prince rocks!

Thanks Ann! Glad you like it! Prince = legendary!