#3: More Programmatic Stocks Coming to the Public Party

How does our pure-play programmatic portfolio work? Where is the buyer vs. seller dividing line? What are unit economics? What the heck is a SPAC?

Welcome to Quo Vadis, your periodic source for fresh programmatic news and off-the-beaten-path perspective. If someone was kind enough to share this with you, then you’re in luck! Just click here to join the conversation.

Happy Pi Day! For any circle, big or small, just divide the circumference (the distance around the circle) by the diameter and you always get exactly the same number. Pi is a totally irrational number, it goes on forever and ever — just like programmatic ad spend.

And as luck would have it, today is also Albert Einstein’s birthday! Einstein’s Theory of Relativity says that E = MC^2 because energy (E) and mass (m) are interchangeable. Quo Vadis wonders if Albert would get a kick out of our Theory of Everything for Programmatic where Impression Value = ∑ (P x Qr/Qe) – P. We think he would!

Programmatic Portfolio Party Comes With Unicorn Club Status (For Some)

Last week, Quo Vadis showcased our core portfolio of 7 pure-play programmatic stocks. It won’t stay at only seven players for much longer — with all the IPOs and SPACs on the horizon, our Quo Vadis portfolio party will very likely grow by 10 to 15 players by year’s end. Maybe more. Quo Vadis subscribers will be the first to know when our portfolio grows. Lucky you!

A few subscribers have asked us to talk about how our equal-dollar programmatic portfolio works and what happens when a new player is added to the party. So let’s do that today!

Our current portfolio has three demand-side players and one neutral party-goer. The three other bon vivants make a living on the supply side.

Demand-side players: TradeDesk, Criteo, and S4 Capital.

First things first: never ever confuse the term demand-side with buy-side. Just because an adtech player fits into an artificial construct that we all call “demand-side” doesn’t mean it’s actually on the buy-side of the trade. Far from it, most of the time.

In reality, the only pure buyer across the entire supply chain is the advertiser. Everyone else is either a pure seller or a quasi-seller.

How do we know this is true? One way or the other — disclosed or not disclosed — supply chain players make money on a percentage of ad spend basis. The advertiser writes the first check, and everyone else gets nourishment as the buck moves down the supply chain. Period. End of story.

So, if you happen to be an advertiser mesmerized into a belief that a given player is a buy-side agent on your side, then you create the perfect circumstances to get totally arbitraged and never even know it happens billions of times every day.

Rule of thumb: Any time one of these sellers wants to get kinky and dress up in buyer clothes, just start humming Fleetwood Mac’s “Sweet Little Lies.” It’s a great tune, and it will make you feel really good in the way only ‘80s music can.

Tell me lies, tell me sweet little lies. Tell me lies. Tell me, tell me lies. Oh no-no, you can't disguise. You can't disguise. No, you can't disguise. Tell me lies, tell me sweet little lies.

The TradeDesk

Besides Google’s DV360 and Amazon’s homegrown DSP, The TradeDesk is by far the biggest on the open web, with over $4 billion in ad budget flowing through its programmatic pipes.

As far as the open web programmatic playground goes, TradeDesk is our Unicorn Club leader, touching more than one billion in ad budget.

Rule of thumb: Quo Vadis analysis tells us that investors will give $11 in valuation for every $1 in ad spend moving through a player’s programmatic pipes. Mo’ ad spend, mo’ money.

Criteo

When it comes to ad budget, Criteo is also relatively big, with $2 billion in ad money pumping through its machine learning engine. Before all the cookie troubles, Criteo used to “see” $2.5 billion in ad money, but it’s still safely in the unicorn clubhouse.

We suspect Criteo will regain ad dollar momentum as they reposition for massive e-retail growth.

What the heck is e-retail? When you go shopping around Walmart.com, the website works double-time as an e-commerce experience as well as a publisher selling ads to soap brands, dog food companies, and all the other 75 million skus on its virtual shelves. Criteo acquired a company called HookLogic for $250 million in 2016… it’s payoff time now.

S4 Capital

S4 is an enigma, which is quite fitting since programmatic advertising is like a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma. At least that’s how Winston Churchill would probably describe it.

S4 is a new kind of holding company in every way. It’s part media agency, part creative, part consultancy, part DSP-ish as a top Google reseller, and 100% digital, with zero legacy assets.

S4 is very different in terms of holdco structure as well. When they acquire companies, they do so based on a unitary structure instead of a typical earnout model. Think of unitary structure as a canoe — if anyone stands up, it tips over. Earnout models have the opposite effect because you have to paddle standing up the whole time — it’s an incentive disaster waiting to happen.

According to their financials, they’ll do $155 million USD in programmatic net revenue. So, if we assume a 15% take-rate on media fees, then S4 is almost certainly in the Unicorn Club, with just over $1 billion in media budget under management.

Compared to legacy holding companies, S4 is doing really well. Investors love it. We expect legacy agency models to imitate S4’s canoe and row fast as they can.

Media-neutral player: Liveramp

Liveramp is the only media-neutral company in our portfolio, at least for now. But who knows — with companies like InfoSum raising an easy $23M in venture cash and recruiting an A-list leader like Brian Lesser, raising a few hundred million more and getting on the SPAC train does not seem like much of a jump.

Liveramp empowers advertisers with audience data tools to connect with consumers vis-à-vis programmatic ads. While Liveramp is not a total pure-play programmatic company, public filings make it clear that its growth and data usage are directly tied to programmatic media.

“We work with over 50 clients paying us $1 million or more, and as we continue to expand our coverage beyond programmatic, we expect to see this number grow… historically, our focus has been to enable data-driven advertising in the programmatic space.” See page 14 of Liveramp’s 2020 10-K Report, if you’re into that kind of thing.

Supply-side players: Magnite, Ruko, and Pubmatic.

Magnite

Over the past two years, Magnite has driven more gains across our portfolio than any other player, including The TradeDesk.

Magnite’s consolidation strategy seems to be working well. In a space with literally hundreds of SSPs, there are a few big ones like Magnite, while all the rest either get sucked up or sent up shit creek without a paddle.

Magnite got bigger, mightier, and purportedly more cost-efficient when management merged Rubicon Project + Telaria and then re-branded as Magnite in December 2019, creating ‘The Trade Desk of the sell-side.”

And just a few weeks ago, Magnite agreed to acquire SpotX, a Denver-based SSP, for $1.2 billion. The deal is not yet complete, so there’s still a decent chance the price tag gets cut or the deal falls through.

With such a lofty valuation for such a small DSP, we started to wonder: “Is SpotX in the billion-dollar unicorn club?” We ran the numbers. The short answer is, “No, not even close.”

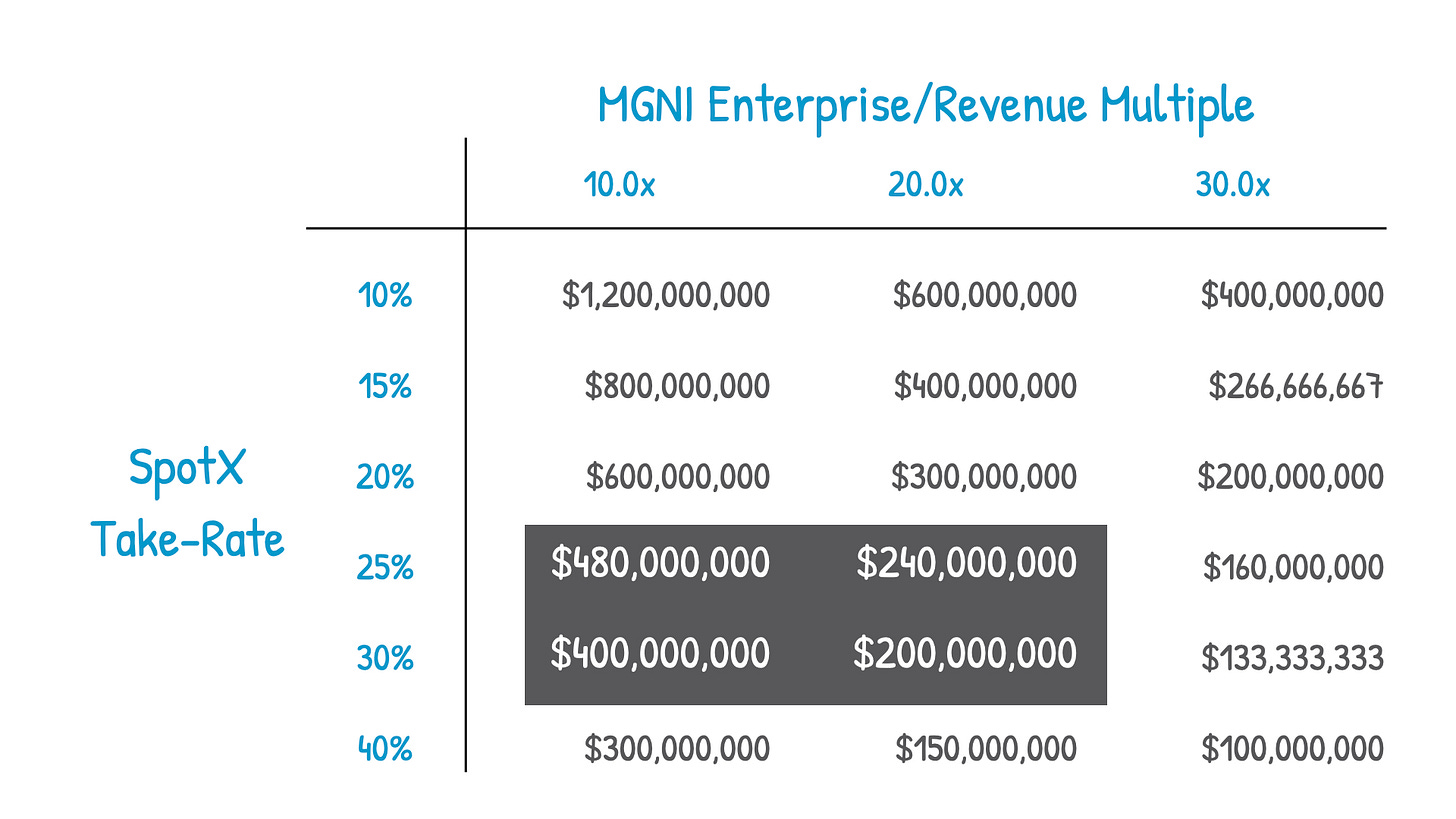

At the time of the SpotX acquisition, Magnite was trading at 25x Enterprise Value (i.e., market cap plus debt less cash). So let’s get a bit crazy and say management broke Tony Montana’s #1 rule in Scarface, “Don’t get high on your own trading multiples.” If they did, it tells us that SpotX’s ex-tac revenue is around $48M.

Now comes the tricky part: take-rates. Nobody outside of Magnite — or any other SSP — knows what an SSP actually earns in terms of the percentage fees they “take” when they sell a publisher’s inventory to a DSP.

Not knowing is okay with us. We can take a really good guess, and you get to decide for yourself if we are nuts or close enough.

Rule of thumb: In public forums, most SSPs will say their take-rates are 15% max. Quo Vadis recommends taking 15% fees with a hefty grain of salt. Real take-rates could be much higher if undisclosed fees or the dark art double-entry accounting tricks come into play.

Perhaps the best proxy on take-rates was published all the way back in 2017, when Rubicon Project (aka Magnite) “slashed its take-rate in half, to 10% to 12%, by doing away with buy-side fees.” So, with $48 in ex-tac in revenue on 15% take-rates, SpotX would touch around $320 million in ad spend. In a market where roughly $50B is moving through DSPs, that sounds like peanuts to us.

Unicorn Club status is not everything. The thesis behind the SpotX acquisition is all about CTV strategy, so who knows — maybe SpotX has some amazing video inventory that somehow no one else in programmatic land has. We know that sounds like a hard sell, but it usually works in the programmatic space.

What Would Ray Dalio Think?

If we put on our Ray Dalio hedge fund hats and make a probability-based guess, we’d estimate that SpotX sees around $200 million to $480 million in ad inventory. Real take-rates are probably much higher than 15% in order for an SSP to price its services above marginal cost (i.e., the variable cost to process the next ad impression), and Magnite’s management probably paid a bit less than its own trading multiples.

Either way, Magnite is certainly in the Unicorn Club. With $221 million in 2020 revenue and 10% assumed take-rates, they handle over $2 billion in ad spend.

Back in 2018 when Magnite was just the Rubicon Project (before merging with Telaria), they already handled $992 million in ad spend (see 2018 10K report, page 60). Add in a few hundred million with SpotX and Magnite is probably in the #2 unicorn position behind TradeDesk and one spot ahead of Criteo.

Roku

Some folks might wonder why we include a streaming company in our programmatic portfolio. So why do we? Good question, we’re glad you asked.

With Roku’s 2019 acquisition of DataXu (a DSP platform), plus the one foot they already have in the programmatic space as an SSP, the company is very much dependent on programmatic growth and praying that a big bet on CTV ads will pay off.

Programmatic is so important to Roku’s success that they called it out six times in their 2020 report, four times in 2019, and just two times in their 2018 report. I wonder how many mentions it will get next year — we’re going with eight!

Is Roku in the programmatic unicorn club? We have no idea. There is no good way to tell from their public filings. Here’s what we can tell — Roku does $1.8 billion in total net revenue, and 71% comes from a mixed bag of what they call platform revenue. That’s roughly $1.3 billion. So, the only way Roku makes it into the clubhouse is if 75% or more is sold via programmatic exchanges. It’s highly unlikely, so Roku will have to apply again next year.

Pubmatic

Pubmatic, the supply-side platform founded all the way back in 2006, had a successful IPO in December 2020. As of February 26, 2021, the stock was up 163% since its IPO day and up 63% in February alone.

Alas, when Google spoiled the party with its existential identity crisis announcement in early March, Pubmatic lost about 30% of its value overnight. The stock is still trading way above its IPO price, which is pretty good considering their highly exposed to identity resolution in the bid stream.

But is Pubmatic in the Unicorn Club? With just $149 million in ex-tac revenue earned from their “take-rate”, it’s not clear if Pubmatic qualifies for membership.

On one hand, if Pubmatic’s take-rates are ~15%, then they might squeak into the club. On the other, while anything lower than 15% gets them into the club, low take-rates that are too low don’t bode too well for valuation growth over time, particularly as price competition and transparency demands get tighter. In other words, the lower the take-rate, the more difficult it becomes to generate the kinds of profits and cash flow Wall Street requires to stay interested.

Anyone keeping an eye on programmatic ad stocks must have been scratching their head at valuation discrepancies. For instance, the market is somehow valuing Pubmatic 37% higher than Criteo, despite Criteo doing a few important things way better… if you’re interested in value creation, of course.

Case & Point: Criteo generates 5x more ex-tac revenue, 5x more earnings, and has 6x more cash on its balance sheet. And when it comes to the granddaddy of valuation (cash creation), Criteo’s machine pushes out 1.5x more cash than Pubmatic.

It’s adtech, so go figure. The good news is that sometimes markets get a little too giddy on tech stocks, but they always come back to reality at some point.

Unit Economics

When it comes to analyzing and comparing the fruits of peer companies, there is no sweeter data point than getting insight into unit economics.

For all you newbies to economics, don’t be afraid. Unit economics are really simple.

Think of it this way. Whatever unit comes off the production line, that’s unit economics. You see, that was painless.

Here’s a good example: Reese’s has a factory producing delicious and nutritious peanut butter cups. That’s the unit of interest. Every time they produce more, their total costs go up a little, but their marginal cost — the cost to make that one extra peanut butter cup — goes down. This means they make more profits.

With programmatic companies, peanut butter cups are expressed in terms of impressions bought or sold, or perhaps the number of bid requests processed.

This kind of data point is incredibly hard to come by because it’s a valuable piece of competitive intelligence. Public companies typically don’t like to reveal much about unit economics because they don’t want competitors to know how much real pricing power they have or don’t have.

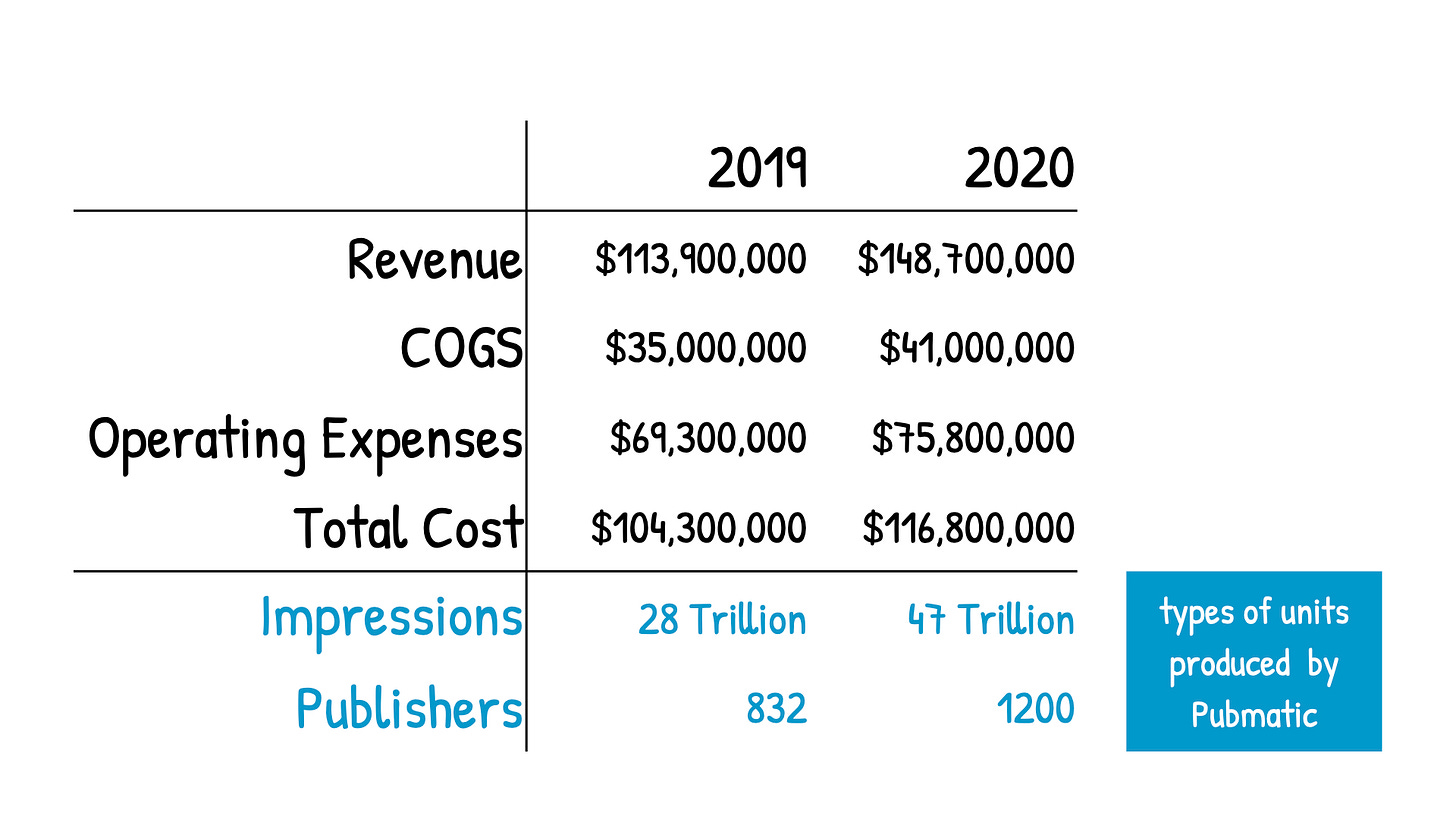

In Pubmatic’s recent 2020 10-K highlights, they put out a unit economic teaser that tickled our fancy, stating that the company:

Processed 46.9 trillion impressions in 2020 — a 69% increase over 2019 — and increased new platform capacity throughout the year;

Added 368 new publishing partners in 2020. Today, we work with over 1,200 publishers and app developers, including mobile websites, app, and CTV properties.

We took the tease and came up with a neat table to get a glimpse of Pubmatic’s unit economics.

What did we learn?

Sure, it’s only two data points, but we’ll take what we can to estimate Pubmatic’s marginal cost per impression at $0.0000007. If you split a penny 1.5 million times, that’s how much it costs for Pubmatic to process a single bid request.

Programmatic companies make money from decimal dust, so if you can’t run a tight ship, you’ll take on water and sink like a Rocket Fuel (we couldn’t resist that one!)

Let’s take it one step further. We can also estimate the price Pubmatic charges publishers per impression, which is a roundabout way of talking about marginal revenue.

Our two-data point model says Pubmatic charges $0.00000341 per impression. Just split a penny three hundred thousand times and you’ll get there.

Anyway, the important thing is that the price Pubmatic charges publishers indicate a contribution margin of 4x over cost. That’s a lot of directional pricing power, so perhaps real take-rates are probably really healthy.

Want to know more? We thought you would. With this tiny dose of directional data, we can also estimate that Pubmatic’s annualized fixed cost is around $86 million. That means if every publisher stopped doing business with Pubmatic for an entire year, or if a programmatic pipe burst and they could not process any impressions, they’d still have $86 million to pay people, rent, debt service, etc.

And now the crescendo. If you take $86 million in fixed cost and divide it by contribution margin, you get to see how many impression units Pubmatic needs to process to break even.

Drum roll please 🥁🥁🥁… 31 trillion.

Ideally, you want at least 30 months or more of unit economic data points to get a more accurate regression read. All we have is two, but we’ll take it to at least get a directional read.

Counting impressions is not the only way to study programmatic unit economics. You can also go high-level by just looking at customer counts, such as publishers doing business with Pubmatic. If we did that, we’d learn a few neat things:

Every time Pubmatic onboards a new publisher, it costs them an extra $34K in marginal cost terms.

And every time they land a new publisher, they charge $133K per year, so their contribution margin is $94K. Not too shabby.

That means Pubmatic started to break even with around 800 publishers — the rest is gravy.

Coming in April: Criteo provides the most data on unit economics across all of programmatic land. If you subscribe to Quo Vadis+ and you’ll get our deep dive Criteo model + commentary. We disentangle and unlock the infamous “15% unknown delta” highlighted in ISBA/PwC’s May 2020 investigation on programmatic transparency.

How Do We Fit In a New Player To Our Growing Portfolio?

With so many adtech SPACs and IPOs planned for 2021, our Little Portfolio That Could will add a few more cars. 🚂🚃🚃🚃🚃🚃🚃🚃...🚃🚃...🚃… Choo choo! We can hardly wait!

A few Quo Vadis subscribers have asked us, “How do you adjust your equal-dollar portfolio to fit in these new players?”

Great question. Let’s take S4 Capital to show how simple it is.

Let’s Go Back In Time

Our Quo Vadis Portfolio started in January 2018, but S4 was not added until November 2018.

Before S4 joined the party, our portfolio contained just five players (TradeDesk, Criteo, Liveramp, Magnite, and Roku).

We started with $100 in Monopoly money, divided it up into five $20 tranches, and “bought” shares for each of the five companies starting in January 2018.

When S4 came along in November 2018, we now had six companies in our Little Portfolio That Could.

To make room for S4 — while still preserving our portfolio balance — we go back in time and pretend as if we had six companies all along. Instead of allocating $20 each, we’d now have to allocate $16.67 each.

We accommodate this adjustment by selling off a proportional amount of the original five stocks as if they were each contributing an equally weighted share to fund the $16.67 needed to buy shares in S4 Capital ($100 ➗6).

When Pubmatic came along over a year later, the portfolio grew from six stocks to seven, so we ran the same adjustment to come up with $14.28 ($100 ➗7) in new Monopoly money to buy PUBM’s stock on an equal-dollar basis.

So, for all our friends in the UK, “Bob’s Your Uncle!”

Theory of Everything for Programmatic

Did you think we’d leave you hanging? It would be rude to flash the most powerful, and the most under-used formula in all of programmatic, and not tell you more about it.

If you want to learn more, then just read Programmatic Lemon Market Game. It’s all there!

TL;DR

Imagine you’re willing to pay a $10 CPM for average ad quality, $20 for perfect ad quality, and $0 for the total absence of ad quality.

Now imagine your DSP gets a bid request, but you’re not allowed to know as much as you’d like about potential ad quality.

You do the foolish thing and bid $20 anyway.

You find out afterward that you only got average ad quality.

With better information, you would have only paid the intrinsic price of $10.

Therefore, ($20 price paid x $10/$20) – $20 = –$10 in value destruction.

If this negative-sum outcome happens more often than not (aka winner’s curse), then you’re playing the programmatic game all wrong and should probably exit until you figure out how to win (and know that how much you won).

Of course, if you’ve escalated commitment to spending ear-marked ad budget within a set time frame (aka pacing, scaling, heavying up, etc.), then you’re caught up in the “the Struggle”. Unless you like struggling, read more here.

Ask Us Anything (About Programmatic)

If you are confused about something, a bunch of other folks are probably confused about the same exact thing. So here’s a no-judgment way to learn more about the programmatic ad world. Ask us anything about the wide world of programmatic, and we’ll select a few questions to answer in our next newsletter.

Join Our Growing Quo Vadis Community

Was this email forwarded to you? Sign up for our monthly newsletter here.

Get Quo Vadis+

When you join our paid subscription, you get at least one new tool every month that will help you make better decisions about programmatic ad strategy.

Off-the-beaten-path models and analysis of publicly traded programmatic companies.

Frameworks to disentangle supply chain cost into radical transparency.

Practical campaign use cases for rapid testing and learning.

hey guys, I'm a little confused with how the Pubmatic calculations were arrived at. Can you share this please? Thanks