#18: In-House Migration Path (Part 2/3)

Halfway House; Getting Scientific; Working Media Savings vs. Found Money

Welcome to Quo Vadis, your periodic source for fresh programmatic news and off-the-beaten-path perspective. Click here to join the conversation.

Today is National Fluffernutter Day! Who knew!? But the great news for our Quo Vadis subscribers is that every day in Programmaticland is a Fluffernutter Day... except for when they read Quo Vadis! And today we have some extra special no-fluff content for you on In-Housing — enjoy!

But wait… there’s more! Along the in-house journey, advertisers and practitioners will no doubt hear big words like “AI” and “custom algorithm.” Join our Use Case Interview with Eric Schwartz from Scibids on October 20 to get the real scoop. No fluff, guaranteed! Register here today!

In-house Migration Path (revisited)

In the first part of our in-housing series, we introduced a framework called the In-house Migration Path. It’s a simple model to illustrate the route advertisers follow as they take programmatic media operations in-house.

1. Starting Point

This is where most large advertisers start out.

They usually rely on media agency staff to run and report on programmatic campaigns.

The agency owns all (or most) of the adtech contracts that provide “easy button” technology. It’s “easy” because that’s how it’s sold. With just a few keystrokes, the phenomenon of incredible advertising ROI happens like magic.

2. Halfway House

Eventually, trade press articles, investigations, and industry association research awaken clients to the reality that they have mice in their programmatic house. So, they do what people do — they look for a mousetrap.

Finding the right programmatic mousetrap is not easy, so advertisers create an internal task force and/or hire outside consultants to look into what’s going on.

Unfortunately, marketers tend to break rule #7 in the Eight Rules from Carney (from Ben Mezrich’s book Ugly Americans), “The first place to look for a solution is within the problem itself” (the other 7 rules apply to programmaticland too).

In any case, they want to know:

Where is my programmatic money going?

Answer: It’s probably not buying real ads, to real people. Ozy Media’s glorious collapse showed the world once again the ugly underbelly of programmatic fundamentals.

Is my money going to supply chain fees or working media?

Answer: The former is the supply chain's objective, the latter is not.

What do we need to change (tech, processes, people) to increase working media?

Answer: Use technology to bid what the ad quality is worth and employee people interested in measurable advertising outcomes to show you the difference.

Getting from the Starting Point to Halfway House is a tremendous amount of work for large advertisers, and it’s usually quite time-consuming (it can easily take 12 months or more.)

Even though industry surveys and the trade press like to dramatize in-housing as a monumental shift disrupting the media agency model, the truth on the ground is almost always a story about halfway-housing.

Case and Point: August 2020 headline from AdExchanger:

“No Longer The Exception: 69% Of Brands In-House Programmatic"

Translation: 69% of brands surveyed made it to the Halfway House. They start by contracting directly with the same “easy button” technologies their media agencies used, but the same agency staffers still own campaign setup, execution, and most importantly, reporting.

3. House Talent

In a few rare cases, advertisers hire a seasoned programmatic manager who has hands-on-keyboard (HOK) experience from previous roles and knows pretty much everything on AdOps Insider. More often than not, this in-house manager’s previous job was probably at a media agency. Since brands pay higher salaries, the jump is easy to make particularly for cream-of-the-crop talent.

With a well-paid manager in play, a core team of junior HOK staffers is recruited, usually from media agencies and sometimes adtech companies.

But after all the interviewing, planning, and promises (or hope) of programmatic excellence, not much actually changes. If the in-house team still chases vanity ROI metrics (the kind that drives finance people nuts) and if procurement still chases CPM targets (instead of the best qCPMs), then programmatic-as-usual is still in full swing.

Programmatic-as-Usual is the difference between spending ad budget and proving real ad results, such as incremental sales lift, in return.

4. Destination

In the rarest in-housing case, the ambitious marketing leaders with bosses who are equally risk-tolerant and curious will go for the full monty. Not only do they bring in HOK staff, but they do it with bigger plans in mind.

From the get-go, these brave ones recognize that the easy-button approach is a great way to spend money but a terrible way to get real advertising outcomes. These explorers seek to first break down every aspect of their programmatic supply chain and then build it back up from scratch with scientific thinking and the most state-of-the-art tools.

5. Evolution

As more marketers journey deeper down the migration path, competitive market theory suggests that media agencies will look to offer a comparable alternative.

Just like risk-tolerant in-housers, media shops will increasingly invest in scientific adtech tools not only to replace their labor-dependent model with productivity gains but to upskill their talent bench with better ideas and faster innovation.

As more in-housers head toward the Halfway House and beyond, we expect to see the emergence of more adtech startups with real AI decision-making, more accurate ad quality data, custom algorithms, and the like.

While in-housers will probably be the first to use and master these tools, innovative agencies won’t be far behind as they look to acquire their way into a new future.

In the media world, the competitive race is always characterized by being the company with the least-worst alternative. Whoever gets there first will be the biggest winner.

But, if too much time passes and agency innovation fails to get ahead of the game, in-housing could reach a point of no return.

Time will tell. The clock is ticking fast. If Proctor & Gamble (the world’s biggest advertiser) keeps chipping away at in-housing programmatic that could mean game over. If that happens — and laggard adopters will be sure to follow one by one — in-housing will have its J-curve moment. The rest will be history.

The Journey to the Halfway House is Paved with Working Media

The very first step on the in-house journey usually starts with what industry folks call a working media exercise, also known as a “cost waterfall” study. Here’s what usually happens:

Marketing Procurement gets an industry report claiming “less than half of advertiser ad budgets make it to publishers” and the “the other half is subject to fraudulent and non-viewable impressions.”

When the procurement team shares this news with the brand team, it probably comes as a surprising shock. “How could this be?” they ask, “our media agency is supposed to be on top of this stuff because that’s what our contract agreement says.”

So, everyone agrees that the best step is to hire an outside expert who collects data from the client’s programmatic supply chain “partners,” maps it out, and calculates working media.

When the consultant findings come in, they usually aren’t pretty. As a rule of thumb, overall working media will probably be about 20% at best but it could be less than 5% — yikes! (This step is also known as the “case for change" in consulting speak. More on this in two minutes.)

With a clear lay of the land showing how $1 in ad budget turns into a few cents of actual media buying and real ads to real people, the team (procurement+marketing+consultant) puts together an investment case detailing key changes that will increase working media toward a specific goal. This is known as the “value of change” in consultant speak.

Supply Chain Cost Waterfall

Programmatic cost waterfall charts are a lot like Rod Stewart’s hit 1971 tune “Every Picture Tells a Story”… “Combed my hair in a thousand ways, but I came out looking just the same.”

These so-called cost waterfall exercises can be devised in a variety of slightly different ways, but the end result almost always looks the same — and it ain’t pretty.

Let’s break it down.

The cost waterfall starts when a client allocates ad budget to its media agency of record (AOR). These folks plan and buy media in exchange for a fee.

All in all, you start with $10 in ad budget to buy 1,000 impressions, and after pushing it through a supply chain with many adtech players, something less than $1 comes out the other end.

When the AOR recommends that a portion of the overall budget should go to programmatic ads, they send funds to an agency trading desk (ATD) or programmatic operating unit (POU) within the holding co structure. These folks set up and run programmatic campaigns using data, DSPs, SSPs, ad servers, verification vendors, and publishers.

Since programmatic is synonymous with audience targeting, a portion of the ad budget is used to buy data to make a targetable audience segment. For example, if a CPG has $10 to spend and buys an audience segment from a consumer data provider (Experian, IRI, LiveRamp, etc.) for $1, then 10% of the budget is used up.

With the campaign ready to go live in the DSP, the DSP gets paid on a percentage of the remaining media basis (e.g. ~10% of the remaining media budget). Keep in mind, how much the DSP actually gets is subject to how various accounting elements are treated.

Accounting Term: At this point in the waterfall, we call the remaining ad budget “Funds Available for Auction.”

As ad impressions are offered by SSPs and then bid on and won by a DSP, the SSP gets its share (also known as a “take-rate”), which is also a percentage of media.

Accounting Term: Whatever is left over after the SSP’s take goes to publishers. We call that “Type I Working Media.” In most cases, publishers get between 40 and 60 cents on the dollar and the advertiser gets 1,000 served impressions.

Everything so far is fact-based because someone paid an invoice to someone else in the supply chain. All of it was originally funded by the advertiser, of course. Whether or not the invoices are correct, all-inclusive, or transparent is another matter.

At this point, an advertiser (or at least the shareholders of the company doing the advertising) should want to know how many of the 1,000 impressions were “good enough” to be called advertising. This is where logical thinking and order matter most.

How many impressions were served to bots instead of humans?

How many of the impressions served to humans were viewable? According to the MRC, if 50% of an ad is in view for 1 second, then it’s good enough to be called advertising (David Ogilvy just rolled over in his grave and said “what the f-ck?!” to Bill Bernbach). If all 1,000 impressions are 50% in view and nothing more, then they all pass the MRC test.

The HOK people (agency or in-house) will report that the campaign had top-notch viewability. But from a real-cost perspective, the advertiser effectively gets only 500 impressions. In other words, an advertiser that runs programmatic based on MRC standards is giving up 50% of Type II Working Media from the get-go. We wish we were making this up, but the truth is stranger than fiction in programmaticland.

Okay, so you end up with a portion of impressions that are served to humans and actually had a fair opportunity to be viewable. But what if the ad is served on a porn site or some extremist content or adjacent to a touchy article on a legit news site? Is that wasteful advertising?

“Brand Safety” is a subjective measure any way you cut it. And give Bayes' Theorem, the odds the decision-makers and tech used for Brand Safety is likely wrong.

Accounting Term: At the end of the waterfall, you end up with what we call Type II Working Media.

What’s the best you can do on Type I Working Media?

Programmatic advertising is a pay-to-play world. Since all supply chain partners are knowable by the advertiser and can be contracted with directly (with verifiable terms and accounting procedures like blockchain/DLT, smart contracts, etc.), the very best Type I Working Media is around 65%.

What’s the best you can do on Type II Working Media?

When it comes to maximizing ad quality after the money is spent, assuming the advertiser sets high standards, the theoretical best outcome is 0% waste… if you’re interested in advertising outcomes.

Size of Prize Riddle

Let’s say you’re Mary or Morris Marketer. You run a cost waterfall exercise for your CPG company called ACME and find out that Type II Working Media is just 10%. That’s your case for change.

You’re not happy with 10% so you set a goal of 50% to be reached in 12 months’ time. If you reach this new efficiency level, you’ll have a giant decision to make:

1) Give savings back to your CFO, or

2) Find a way to spend a bunch of found money, or

3) Something in between.

Either way, you end up with the value of change.

1) Give savings back to your CFO

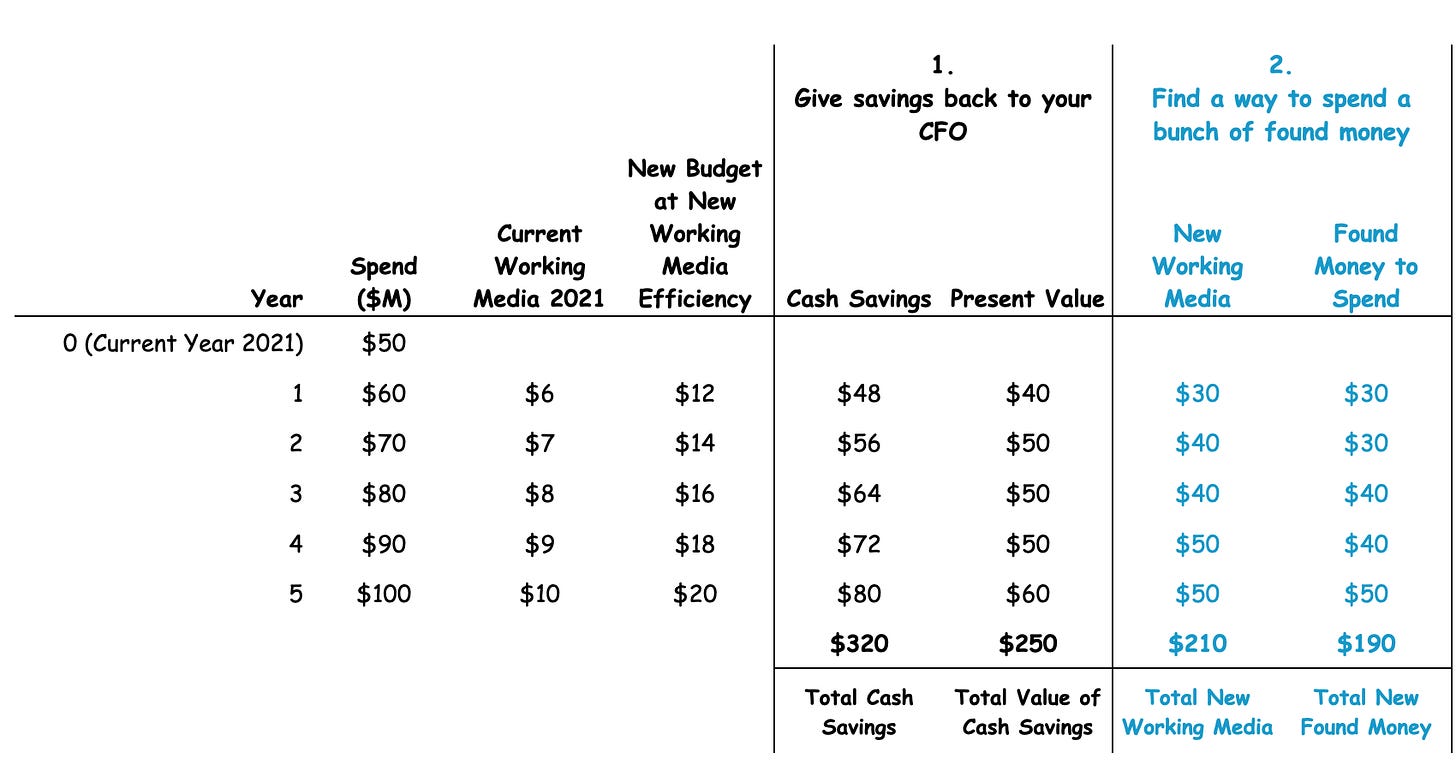

Let’s model it out. Assume ACME will spend $50M on open-web programmatic ads in 2021 (there are likely at least 100 companies or more out there spending $50M or more). Let’s further assume you’re organization also plans on increasing programmatic spend 10% per year over the next five years.

Now, here’s the tricky part that trips people up. If you ended up with $5 million in Type II Working Media before the change, and increase working media to 50%, then going forward you only need to spend $10 million ($5M ÷ 50% = $10M) to get the same amount of quality ads that you got before the change.

So, if you can get the same ad outcome as got before for $10 million instead of $50 million, you save $40 million in real cash money.

Assuming a normal CPG cost of capital at 7%, and if you plan on growing programmatic 10% every year over the next 5 years, the value of cash savings is worth $250 million today. That’s a lot of real money!

2) Find a way to spend a bunch of found money

Alas, the idea of cash savings is not the way advertising thinking usually works. Yes, marketers will always seek to maximize working media, and when they realize these gains, they effectively end up with a ton of “found money”.

This found money must now find a home in terms of buying ad quality, which is one of the scarcest commodities in the world.

Here’s how found money works. If you start with $50 million at 10% working media, and boost it to 50%, you now have $20 million more that needs to find a good home.

$50M x 50% = $25M = New

$50M x 10% = $5M = Old

New – Old = $20M

This is great news for marketers without synthetic CPM targets. They can use the money to pay higher CPMs for the good stuff that actually makes advertising work.

For marketers with synthetic CPM targets, the picture is not so pretty. If the CPM targets are low, which they tend to be, then you end up forcing more money into a supply chain system that will very likely be unable to find enough high-quality inventory. They will gladly take fees for trying.

3) Something in between

The happy place for both marketers and finance folks is to split the money, remove CPM targets in favor of qCPM targets, and go crush it. Once you know how to buy the good stuff in programmatic auctions, then let your competitors buy the bad stuff and be indifferent to everything else.

That’s a dominant strategy in game theory terminology. So, what are you waiting for?

Join Quo Vadis for a Use Case Webinar

With Eric Schwartz, Managing Director at Scibids

In-housing. Agency productivity gains. Getting scientific. Artificial Intelligence. Bidding the intrinsic price.

All these subjects are interconnected. They also get thrown around adtech all the time, but who really does it? Some say they do it, but do they really? Or is it just marketing jargon?

Quo Vadis wants to find out, so we’re interviewing Eric Schwartz from Scibids on October 20th at 10am ET. Register here.

We think Scibids is the real deal. It works with any DS P and creates the circumstances for privileged advantage in competitive bidding environments.

Scientific tools like Scibids usher advertisers through their in-house migration and also give agencies the kind of productivity gains they seek to stay relevant.

Join our conversation and learn more about custom algorithms, how they work, and how you can start testing today.

Whether you’re an in-houser or a media agency, taking a more scientific approach shouldn’t wait!

Ask Us Anything (About Programmatic)

If you are confused about something, a bunch of other folks are probably confused about the same exact thing. So here’s a no-judgment way to learn more about the programmatic ad world. Ask us anything about the wide world of programmatic, and we’ll select a few questions to answer in our next newsletter.

Join Our Growing Quo Vadis Community

Was this email forwarded to you? Sign up for our monthly newsletter here.

Get Quo Vadis+

When you join our paid subscription, you get at least one new tool every month that will help you make better decisions about programmatic ad strategy.

Off-the-beaten-path models and analysis of publicly traded programmatic companies.

Frameworks to disentangle supply chain cost into radical transparency.

Practical campaign use cases for rapid testing and learning.