#69: Quo Vadis SpaceScape — Gravity Theory of Walled Garden Data Trades

Five years ago, the walled garden world did not exist at scale. Only a small handful existed. Now there are hundreds upon hundreds producing tradable data.

Reading Time: 8 gravitating minutes

Quo Vadis is introducing a new spacescape called The Gravity Theory of Walled Garden Data Trades. It’s a model where we theorize how and why hundreds of walled gardens will trade data with each other through a clean room mechanism similar to how and why countries engage in international trade resulting in mutual benefit.

There are a few layers to unpack along with two underlying economic principles in play. We'll unwind the key elements in this post and unpack other nuances in future posts.

First Things First

Let’s unwind the first two topics — comparative advantage and international trade — to form an analogous view illustrating why walled gardens will trade data with each other.

In international trade, countries trade goods with each other because it makes each party better off. The concept of comparative advantage is a key principle that helps explain why countries benefit from trading with each other.

The concept of comparative advantage was first introduced by classical economist David Ricardo to show how trade can create value for both parties even if one country is more efficient at producing everything.

Feel free to geek out: "On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation” David Ricardo, 1817

Let's use a simple example of two made-up countries: Verdantia and Auroria.

Verdentia is very good at making steel. It has the right resources, technology, and skills to produce steel efficiently. Auroria is very good at making butter. It has lush pastures for dairy cows, the right climate, and expertise in dairy farming.

Now, even if Verdantia can produce butter (but less efficiently compared to steel) and Auroria can produce steel (but less efficiently compared to butter), each country has a comparative advantage in producing what it's best at.

Verdentia’s comparative advantage is in producing steel because it sacrifices less butter to produce steel than Auroria would.

Auroria 's comparative advantage is in producing butter because it sacrifices less steel to produce butter than Verdentia would.

If Verdentia focuses on producing steel and Auroria focuses on producing butter, they can produce these goods using fewer resources than if they tried to produce both goods by themselves.

As such, Verdentia can trade some of its steel to Auroria for butter, and Auroria can trade some of its butter to Verdentia for steel.

In the end, both countries get more butter and steel than if they had not traded. This happens because each country is making what it is comparatively better at producing, leading to more efficient production and allowing both countries to be better off.

Put another way, it's like two friends where one is really good at baking cakes and the other is great at making pizza. Even if both can make both dishes, it makes more sense for each to make what they're best at and then share the goodness with each other. Both get to enjoy delicious pizza and cake without putting in extra effort or resources. This is the essence of comparative advantage and international trade.

The Original Gravity Model of Trade

The Gravity Model of Trade is a concept used in the field of international economics to predict bilateral trade flows based on economic size (often measured by GDP) and the distance between two countries. The gravity model states that the volume of trade between two countries is proportional to their economic mass (e.g. GDP) and a measure of their relative proximity.

As you’ve probably guessed, the gravity model draws its name from Newton's Law of Gravity:

Every particle of matter [data] in the universe attracts every other particle [data] with a force that is directly proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between their centers.

— Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, Sir Isaac Newton

Economist Jeffrey Bergstrand’s 1985 paper proved that trade between two countries is directly proportional to their economic mass (GDP) and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them. In words, tell the model the size of two countries and their proximity to one another and it will accurately predict trade between them.

According to Bergstrand’s gravity model, larger economies (with higher GDPs) tend to trade more with each other because they produce and consume more goods and services. (Note that specific economic country structures and similarities also play a crucial role in determining trade flows.)

The model also posits that the greater the distance between two countries [walled gardens], the less they will trade with each other. Distance creates friction like transportation/transmission costs and cultural differences.

Ease of access is also important. Economic integration agreements (e.g. free trade agreements or customs unions) also facilitate trade. These agreements reduce trade barriers, making it easier and more profitable for countries [walled gardens] to trade goods [data] with each other.

Lastly, there is the concept of Factor Endowments (such as labor, capital, and natural resources) which affect trade patterns because countries [walled gardens] tend to trade goods [data] that intensively use their abundant resources [ability to create data].

Increasing Marginal Utility Is A Rare Characteristic

By now you probably see where we are headed. Two key questions naturally arise:

Why would two walled gardens trade data with each other?

How does the trading make each party better off?

In 2007, Brad Burnham from Union Square Ventures wrote an influential blog post called Google’s Data Asset asserting that Google’s enterprise value can be interpreted through the lens of increasing marginal utility.

Data has this really weird quality. In economic terms data has an increasing marginal utility. Anyone who took Econ 101 knows that most physical objects have a decreasing marginal utility. When it is raining my first umbrella keeps me dry, a second may be handy if the first blows out, but a third is unlikely to be used. This is true of shirts, steaks, houses, of almost anything you can think of except data.

Data has the opposite characteristic. Each incremental point of data adds value to the ones you all ready have. It is easy to see this in the context of an advertising network. If the ad network knows that a user is female it can show more relevant ads. But, if the ad network knows that female’s age, it can do even better, and data about location, household income, and recent web sites visited all add value to the existing data points, making it possible to show more and more relevant ads. Google’s services all benefit from additional data albeit in different ways.

Burnham’s explanation helps us understand why, in a world without 3rd party cookies along with an insatiable demand for audience-targeting capabilities across the entire supply chain, two walled gardens will likely want to trade with each other.

For instance, if one walled garden is good at making a certain type of data and another walled garden is good at making another type of data, then perhaps their respective size (measured by data production), proximity (or the inverse of proximity), structure/posture, and having an abundance of certain raw data resources (e.g. processing power, data mining, etc.) are accurate predictors of trading volume between two parties. Is a new market forming before our eyes?

We just had a great leading indicator last week when Liveramp acquired Habu for $200 million. While the trade press might not explain the rationale for such a deal in quite the same way as were are doing here, the underlying thesis of processing or brokering walled garden trades through a clean room mechanism seems like a really big story. Assuming our thesis is in the ball park, it supports Liveramp’s decision to allocate 34% of its cash (plus STI) on a bet that the returns from this new invested capital will beat RAMP’s cost of capital hurdle rate. Quo Vadis likes the expected value calculous.

Rich Ashton at First Party Capital said it best:

“This transaction, completed at a multiple of 11x forward revenues, highlights the immense strategic value that first party data and privacy-preserving tech solutions can bring to incumbent adtech players that need to innovate away from their reliance on cookies, as marketers lose more and more signal.”

NOTE: there are other reasons like establishing an accountant’s value of data as an asset. We’ll cover that topic in a future post

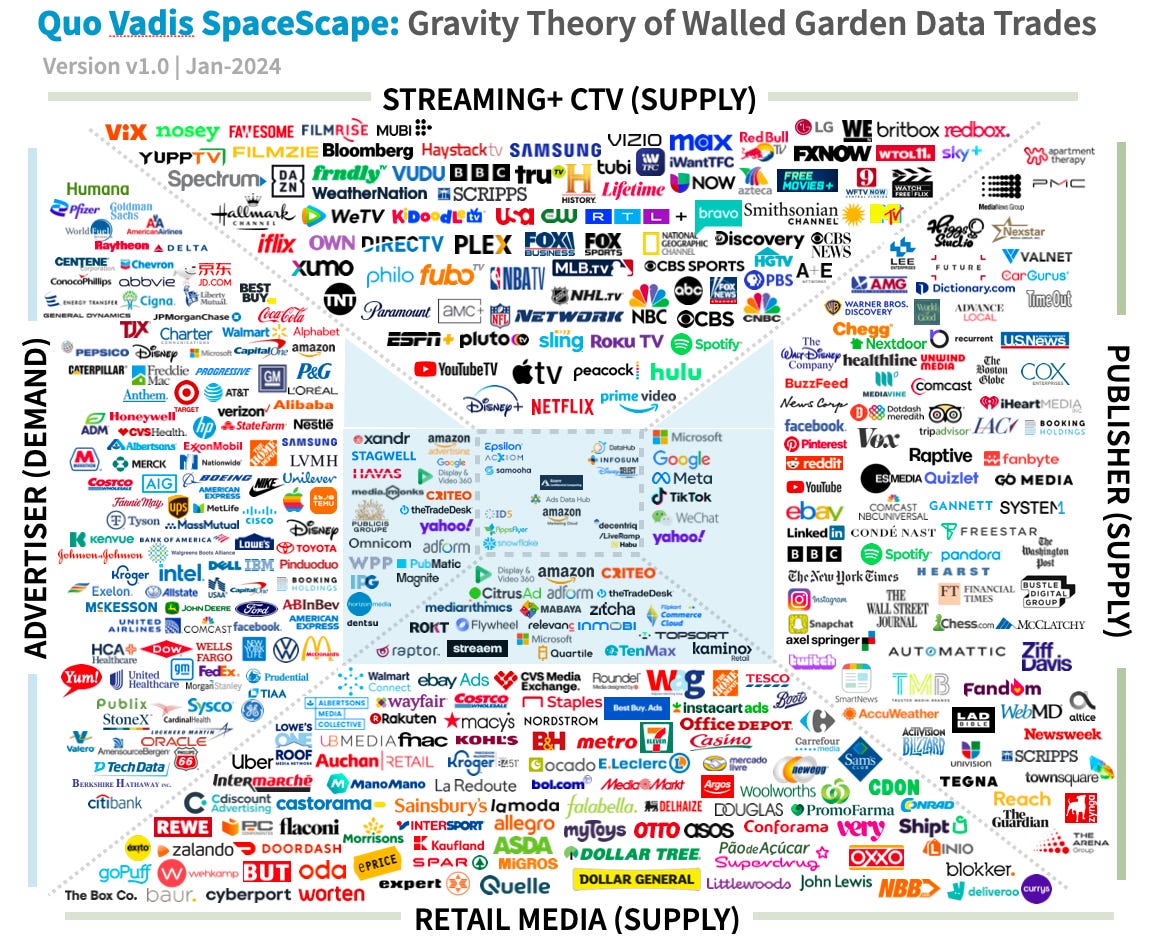

SpaceScape: Gravity Theory of Walled Garden Data Trades

Let’s first frame the parameters of this exciting market landscape and see where we end up. Five player types set the parameters:

Publishers operate websites and sell ads to audiences. These players are placed in the east position. We leaned on Jounce Media’s “bellwether” publishers (media companies) to get a sense of the biggest media brands in the open web publisher world. All of these players used to rely on 3rd party cookies but now lock down their data assets just like classic walled gardens. Also included the big walled garden social media sites like Meta properties and TikTok as well as high-traffic sites like Yahoo and the New York Times. Note that we position only a few big companies in the shaded area close the center. We think these players are well position to play intermediary roles in the data trade.

Streaming CTV players occupy the north sector. We sourced Pixalate’s CTV data to identify the biggest players. It was only a few years ago when just a small handful of CTV streaming apps were around (Netflix, Hulu, Amazon Video, etc). Now there are hundreds of legit players and thousands of others (some of which are dubious). They are all walled gardens. Notably, 70% of consumer time spent on CTV is with the top 10 players.

Retail Media is in the south position. If you’re not familiar with Mimbi (ex-Criteo founder), they produce a nice Airtable data set of the Top 200 retail media playes. The data also includes insights like onsite tech provider (e.g. Criteo, Citrus Ads, TradeDesk, etc.) and other descriptive data. Again, just a few years ago almost none of these retailer media ventures existed but now there are hundreds and growing. They are all walled gardens.

Great Example of a Small Walled Garden Data Trader: Check out how a “How A Gym Chain Became An Ad Data Seller.”

Last but not least, Advertisers occupy the west side of the spacescape. We sourced a combination of Semrush’s Top 100 search spenders and Interbrands top brands list. Going back to c.2018 when the industry found out about 3rd party cookie deprecation and loss of audience signal, advertisers began programs to produce direct first-party relationships with consumers usually by capturing an email address or phone number (with opt-in consent) which can be hashed into a usable identifier. For example, P&G has collected more than 1 billion IDs, or profiles to target people with more precision. Just like the three other walled garden categories, this kind of data production did not exist five years ago and all of it is locked down behind a walled garden.

Cleanroom “Market Makers” occupy the center of the spacescape. They are surrounded by the other four constituencies in what is becoming a market for data trades. Similar to Porter’s 5 Forces, the four external forces along with a need to capture increasing marginal utility is pushing on the center causing trading activity.

For example, early this month eMarketer published their view in “Ad platforms will capitalize on the power of partnerships in 2024” specifally calling out, “[partnerships] can also offer opportunities to share first-party data, like Walmart’s partnership with NBCUniversal, where the latter could take advantage of Walmart’s rich retail media data.

There are only a handful of cleanrooms in the center. We view them as clearing houses, market-makers, dealers, brokers or all of the above. Their job is match and facilitate transactions between two trading parties in a privacy clean way. As long as the mututal benefits of comparative advantage prevail it’s hard not to imagine a massive market opportunity unfolding in real time.

What other clean room companies should be included in our spacescape?

More To Unwind With Walled Garden Data Trades

The concept of walled garden data trades is certainly compelling and appears to be happening. Today we touched on just one use case — capturing and maximizing audience data for targeting — but there are other very interesting cases where trading data adds tremendous value. Quo Vadis will dig deeper on this fascinating space in future posts.

Where’s Wally? How many companies play in at least four of the zones?

Ask Us Anything (About Programmatic)

If you are confused about something, a bunch of other folks are probably confused about the same exact thing. So here’s a no-judgment way to learn more about the programmatic ad world. Ask us anything about the wide world of programmatic, and we’ll select a few questions to answer in our next newsletter.

Join Our Growing Quo Vadis Community

Was this email forwarded to you? Sign up for our monthly newsletter here.

Get Quo Vadis+

When you join our paid subscription, you get at least one new tool every month that will help you make better decisions about programmatic ad strategy.

Off-the-beaten-path models and analysis of publicly traded programmatic companies.

Frameworks to disentangle supply chain cost into radical transparency.

Practical campaign use cases for rapid testing and learning.

Disclaimer: This post, and any other post from Quo Vadis, should not be considered investment advice. This content is for informational purposes only. You should not construe this information, or any other material from Quo Vadis, as investment, financial, or any other form of advice.