Reading Time: 6 equilibrious minutes.

What’s going on?

Never a dull moment in Programmatic Land. Starting this month, The Trade Desk TTD 0.00%↑ is no longer letting publishers (and their SSPs) dictate floor prices to influence bids.

“The Trade Desk is now sending out all bids on behalf of its clients whose campaigns match the inventory up for sale, even if their bids are below the price point at which publishers and SSPs value the inventory” — Digiday.

Recall that programmatic ads are sold in first-price auctions (highest bid wins) where sellers use price floors to set the minimum acceptable rate. TTD’s plan is to bid below the floor price anyway to force their buys into a lower market equilibrium price.

Some folks think this is an explicit move to squash SSP or reduce SSP take rates. For instance, Digiday’s coverage said,

“Nearly all of the execs interviewed for this story agreed that SSPs and resellers are in a position to lose out on revenue from this change.”

Another astute point of view comes from Jana Meron — a programmatic and data strategy consultant at Lioness Strategies:

“Open Path’s rev share is very low, lower than even the best deal a pub [sic] could get from an SSP. The only impact this will have on publishers is if TTD is successful at getting [SSPs] to lower their take rate. The average is around 20%… If the SSPs lower their take rates to 15% or 10% then pubs will make more money but it has nothing to do with the floors.”

If it all plays out as planned, then lower SSP take rates would add more pressure on net revenue for SSP businesses that already have a hard time reaching operating profitability let alone generating meaningful free cash flow.

Quo Vadis has a different view. While these competitive outcomes might prevail, we think any demise SSP might face is just a byproduct of something more fundamental happening with supply and demand.

What does it mean?

Incentives matter. Incentives drive behaviors. And those behaviors tend to shift supply and demand.

Let’s start with demand in Programmatic Land and define it as the demand for cheap-reach inventory. What is “cheap-reach?” Cheap reach is when marketing procurement folks are incentivized to cap CPMs that the advertiser is willing to pay for display ads (e.g. banners and online video), typically on the low end of the range (e.g. ~$1.50).

In other words, allocating ad budgets to programmatic can be viewed as a mechanism to reduce the overall average CPM paid across more premium media types (Linear TV, CTV, OOH, direct premium display ads, etc.).

It is critical for advertisers and investors to note that the demand curve for high-end linear TV is not the same as the demand curve for cheap-reach programmatic ads. How do we know this to be true? Just look at any media plan and you’ll see how all the different media types are split out and then managed by different media buyer skill sets who in turn play in different supply markets to get what they want.

In any case, where there is demand someone will usually supply it. In the programmatic advertising world, inventory owners of all types will gladly supply cheap-reach inventory to your heart’s content.

In the initial state, before TTD made its strategic change, the market for cheap reach was in harmonic equilibrium and floor prices didn’t matter very much. But then something happened, perhaps very slowly and then all at once.

That something is called a “shock.” Over the past five years or so, programmatic has been plagued with one story after the other about ad quality leaving many marketers in doubt. More recently, new stories have piled on a few extra straws that might be getting close to breaking the camel’s back.

YouTube ads running on junk network inventory.

Estimates from Jounce Media that 30% of auction ad requests are from made-for-advertising sites (MFA).

“CTV Ad Fraud Surges with a 69% Increase in Bot Fraud in 2022 and Significant Growth in CTV Fraud Schemes” — (DoubleVerify)

The list goes on if you bother to look. With so much data out there, it’s not hard to test ad quality against the perception-shaping that takes place to maintain programmatic religious beliefs. Like we always say at Quo Vadis:

“There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.” — Shakespeare, Hamlet.

Given all the pent-up angst, marketers might finally be putting their foot down with media agency buyers (behind the scenes, of course), resulting in a cascading effect where both buy-side and sell-side tech players (DSPs and SSPs) feel increasingly compelled to implement technologies to block all this bad inventory.

When bad or junk inventory is blocked, the supply curve gets “shocked” and shifts backward to the left from Point 1 to Point 2. Two consequences emerge:

The quantity of cheap reach supply is reduced from q0 to q1

The price of cheap reach inventory increases from p0 to p1 (Point 2)

Now we have a dilemma to deal with. Cheap-reach inventory happens to come with a low natural tolerance for price increases which creates a marketer-to-procurement dilemma. One side wants to avoid buying low-quality inventory while the other is mandated to keep prices low.

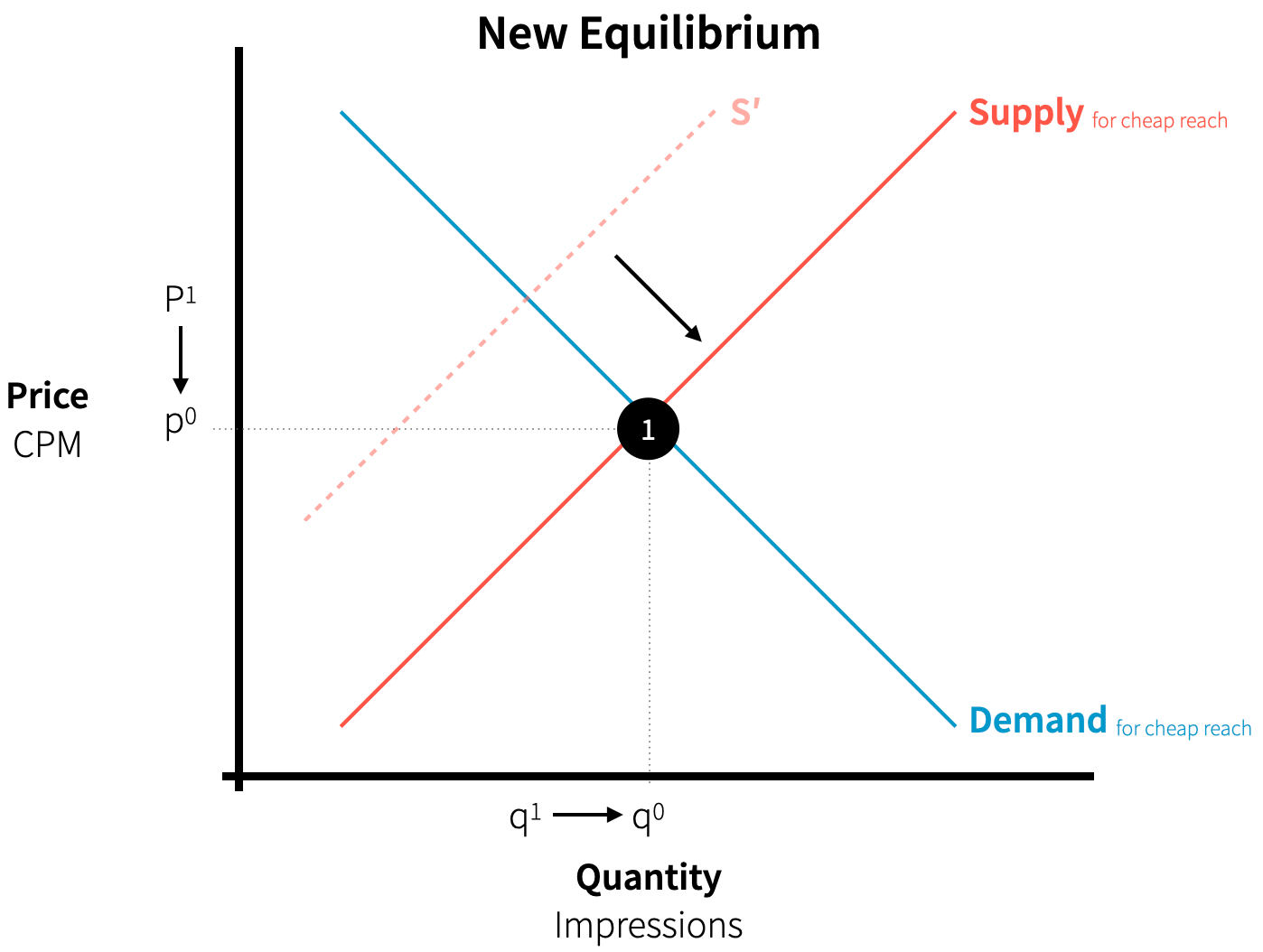

Something has to give. When a big buyer like TTD decides to bid below floor prices, the net effect brings the supply curve back to where it was before at the original lower price point while the quantity of cheap reach supplied also goes back to its original state.

Voilà. The two primary parties get what they want (at least on paper):

Marketers look like responsible media buyers who are not interested in junk quality even though they somehow end up buying it in different repackaged forms.

Procurement can show the finance people that they are meeting internal CPM targets.

The Trade Desk gets to kill a few birds with one stone:

SSPs feel pressure to lower take rates which helps TTD preserve its own ~20% take rates.

Publishers feel more pressure to sell directly to DSPs like the Trade Desk without the need for an SSP intermediary.

Why should “I” care?

If you’re an advertiser, you should care because the constant quest for cheap reach is like a one-legged duck swimming in a circle. Common sense should indicate by now that buying low-quality impressions tends to decrease the probability of driving incremental impact. If you’re paying attention, that’s the opposite of advertising.

Attention Metrics: Read this research by WARC and Lumen Research. If this doesn't convince you that cheap reach is actually very expensive, then nothing will.

If you're a marketer feeling trapped because you need to show ROI performance (e.g. make the numbers look good) but procurement hadcuffs you with cheap reach CPMs targets which have almost no chance of delivering performance, then use attention metrics to gain a fungible view with standarized pricing units across all media types. When you think in terms of CPMs you've already lost the programmatic auction game. When you think and bid in qCPM terms using attention units, you win before the game starts. If you’re an investor, then you’re on the other side. The more adtech players (and media advisors) can push the virtues of cheap reach by dressing it up like a Barbie Doll, the more impression volume runs through the “adtech factory” which in turn reduces marginal cost and increases the probability of capturing contribution margin. That’s the name of the game for adtech.

Therein lies the rub. What’s good for programmatic advertisers is bad for adtech investors and vice versa. If advertiser goals and incentives are at odds with what investors need to see from adtech companies, then investors should think about how sustainable or unsustainable that situation might be. Advertisers can be a fickle bunch and might decide enough is enough on all the shenanigans. Then again, if a behavioral change has not happened yet with marketers then it might not happen at all. That’s probably a good thing for investors.

In an ideal world, marketers would eventually get “real” on open web programmatic advertising and CFOs would eventually interpret cheap reach tricks as wasted shareholder cash. A flight to quality would take off causing profound changes across adtech. At that point, the demand for cheap inventory would decrease to a low enough price point such that these low-end suppliers would no longer be profitable and exit the market.

“Only when the tide goes out do you learn who has been swimming naked” (Warren Buffett). For adtech players built on cheap reach unit economics, they’d probably have to exit the market too.

Ask Us Anything (About Programmatic)

If you are confused about something, a bunch of other folks are probably confused about the same exact thing. So here’s a no-judgment way to learn more about the programmatic ad world. Ask us anything about the wide world of programmatic, and we’ll select a few questions to answer in our next newsletter.

Join Our Growing Quo Vadis Community

Was this email forwarded to you? Sign up for our monthly newsletter here.

Get Quo Vadis+

When you join our paid subscription, you get at least one new tool every month that will help you make better decisions about programmatic ad strategy.

Off-the-beaten-path models and analysis of publicly traded programmatic companies.

Frameworks to disentangle supply chain cost into radical transparency.

Practical campaign use cases for rapid testing and learning.

Disclaimer: This post, and any other post from Quo Vadis, should not be considered investment advice. This content is for informational purposes only. You should not construe this information, or any other material from Quo Vadis, as investment, financial, or any other form of advice.

Interesting point on measuring attentive seconds vs impressions. What (if anything) do you thinks get the ecosystem to move to this? Do you think 3 years from now we'll be in the same place?