#30: Q2 2022 Portfolio Rundown

Portfolio returns down from 334% after Q1 earnings to 309% after Q2 earnings; Looking at adtech through "the Struggle" trade-off framework

FYI — How does all that programmatic auction data-crunching damage the environment with excess CO2 emissions? How can adtech companies offset it? Wanna find out? Join Quo Vadis on Sept 15 at 11 a.m. ET for our Q2 Quarterly AdTech Review with special guest Brian O’Kelley, Founder/CEO of Scope3.

Reading Time: 12 minutes

The information in our newsletter is not intended to constitute professional investment advice.

Where do they stand?

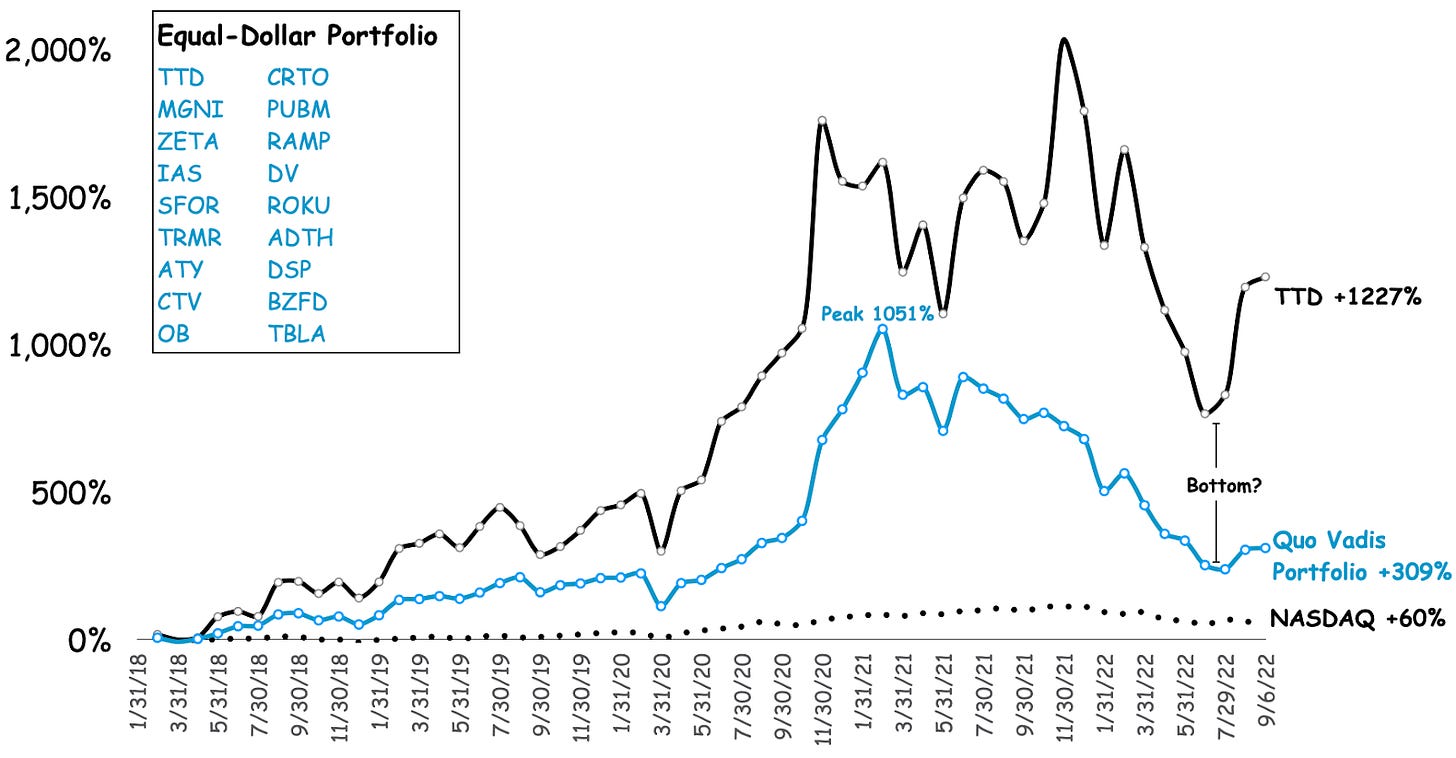

Had you bet $100 in January 2018 when our Quo Vadis portfolio started, you’d be up $309 today. Had you sold the portfolio in February 2021, you’d be up 1000% instead of thinking the adtech spaceship would go up forever.

Like they say, “Be greedy in times of fear and fearful in times of greed.” If the current macro outlook is any indication as we head into Q4 ad spending, then it looks like a pretty good time to play a greed card at what might be the bottom of adtech valuations.

Then again, if advertisers pull back on ad budgets thinking consumers won’t show up during the holiday season, then new lows are on the horizon.

Last quarter, only 5 out of the 18 adtech companies we track were in positive territory. It’s now down to just 4 after Q2 earnings.

The Trade Desk is still the fastest/biggest horse in the race, putting out a Q2 performance that beat consensus — and our model too.

When you look at which adtech player contributes the most to our $309 in total gains, The Trade Desk is the top producer, generating 77% of the gains.

Only 7 players in our adtech portfolio contribute to gains (CRTO, TTD, MGNI, ROKU, RAMP, SFOR, PUBM), while the other 11 are dead weight until they cross the chasm of attracting sufficient ad budget and extracting fair fees from clients and publishers.

Portfolio Trend: Bottom or Faux Bottom?

Our Quo Vadis portfolio has been trending down since February 2021 and appears to have reached a bottom — at least for the time being.

TradeDesk may have reached a bottom, but that could easily change after we see Q3 earnings next month and get a read on planned vs. actual ad spending heading into the Q4 holiday season.

The Conference Board Consumer Confidence Index® increased in August, following three consecutive monthly declines, so Q4 ad spend could turn out to be better than expected. Hard to tell. Nobody knows.

Recall that adtech companies need to do two things all the time: 1) attract ad budget to their platform; and 2) extract fees from it. Besides cost controls, those are the only two levers that matter. If advertisers pull back budgets in Q4, everyone in adtech will get a cold this winter — some worse than others.

AdTech’s Future: A New Lens

Unlike our past quarterly run-downs, we’re doing it a bit differently this time around.

Instead of reviewing Q2 numbers, we’re going to look at our 18 portfolio companies through the lens of the most important programmatic framework: “The Struggle.”

Let us know if you like this approach, and we’ll share the second most important framework when we cover Q3 earnings in October.

The Struggle is based on a core concept from microeconomics called “utility,” or trade-offs. Here’s how it works:

The Struggle presents the programmatic world as a decision based on two “goods” — what advertisers (supposedly) want.

The Y-axis is about wanting to spend big budgets programmatically. That’s the whole point of being a media buyer. e.g. you get ad budget and look to spend it on what you think will generate the best outcome.

Sounds easy, right? It’s not if your aim is to do it really well. The X-axis is about buying some range of ad quality from “crap” (as Marc Pritchard put it) where the chances of getting a fair advertising outcome are nil and buying really great advertising placements that your grandmother would approve of.

Observation suggests that Point A has been the bedrock of the programmatic market. Since everyone in Programmatic Land gets paid on a percentage of media basis, there is a built-in incentive to push volume over quality.

The Other Reason: Crunching auction requests and bid responses is expensive. Driving more volume independent of ad quality pushes margin cost down to a point where adtech firms can compete and turn an economic profit.

It’s nasty out there in a caveat emptor world. For most media buyer setups and mindsets, it’s easier to spend big ad budgets on lower-quality inventory (whether they know it or not), which in turn creates a supply-side incentive to pump and dump all kinds of synthetic inventory into auction exchanges.

At Point A, media buyers manage to spend all the budget just as they are told to by higher-ups, but they end up making a terrible trade-off to get their “advertising” job done. They sacrifice buying the best ad quality — which is a scarce good — in exchange for making sure the budget gets spent on a near-infinite supply curve.

Point B is the opposite. Point B is really hard work stewarded by really smart media buyers who are incentivized to care. It bothers them (and management) if they are sold shiny apples that turn out to be rotten after the fact. Yuck! 🤮

Good apples and bad apples have different prices because they have different quality characteristics. Buying high-quality inventory (humans vs. bots, viewable ads, etc.) results in a probability greater than zero of getting the desired advertising effect. Buying wormy apples has zero chance.

Either way, programmatic supply chain transaction fees are a total certainty. Programmatic sellers extract the same percentage fees (e.g., DSP ~10%+, SSP ~15%+, data sellers 10%+, content verification another 5%+, and ad serving gets a few points too) for processing good and bad inventory alike.

Trade-off Curve 1 is any given advertiser’s starting point. Think of it as how the programmatic market is structured today.

For instance, if you want more of one scarce good (ad inventory), then you have to give up another scarce good (working harder/smarter as a media buyer), resulting in some output level.

Let’s say Curve 1 gets your average big brand advertiser a payoff of 100 units.

Think of “units” as ROI or meeting a defined KPI.

You can spend a ton on poor ad quality or spend a little on high quality and still get the same 100-unit outcome. Doing both is hard work. It’s even more difficult when buyer incentives reward the wrong behaviors.

Trade-off Curve 2 is better because it returns 200 units. But getting there means something fundamental must have changed.

Pushing out trade-off curves toward more outcome units is similar to an efficient frontier.

Nothing exists nor is possible on the right side of a trade-off curve until you actually do something different to get to another curve.

When a media buyer works smarter to find the best inventory and still manages to exhaust a given ad budget as planned, he/she experiences a quantum jump to Point C (these people should be rewarded because they create value).

Not only is Point C better than any point on Curve 1, but any combination of points on Curve 2 is a better place to be because the media buyer gets better advertising outcomes.

The Rundown

Now that you have a good grip on The Struggle, let’s take a stab at understanding our 18 portfolio companies to answer two questions:

Since all value is created in the future, does the adtech player in question need Curve 1 to thrive financially?

Assuming the right incentives are in place, which of our adtech players has the ability/financial structure to shift to Curve 2?

The Trade Desk: If there is a company in our portfolio that has the capital structure and operating system to make the jump from Curve 1 to Curve 2, TTD is certainly the one. With $6.2B in ad flows running through its platform in 2021 and $377M in net revenue in Q2, we estimate $1.51B in FY22 net revenue for TTD. With steady take-rates of around 19%, TTD will see around $7.95B in 2022 ad flows (27% YoY ad flows growth).

Criteo: Given the direct response positioning of Criteo (and its algo engine), it is already naturally positioned on Curve 2 with built-in incentives to keep pushing outward to new curves. Criteo gets paid on clicks, but its customers will keep paying only if those clicks turn into sales conversions. Mathematically, Criteo’s engine bids an auction CPM price where CPM Bid = CPC of the advertiser x predicted CTR of the user. Importantly, the CPM Bid is then multiplied by a ratio of the User’s Average Conversion Rate (a privileged asset across many observations on different campaigns for many different advertisers) divided by the Conversion Rate of the Campaign. In other words, Criteo does better by getting its engine to push the boundaries of the trade-off curve.

Zeta Global and Viant: Although smaller than TTD and Criteo, Zeta and Viant seem fairly well positioned to wean themselves from Curve 1 thinking toward Curve 2 success. Will it be easy? No. Will it take working capital management and a big sales effort to show clients the way to Curve 2 sooner rather than later? Yes.

AdTheorent, Tremor, and AcuityAds: It might sound like tough love, but ADTH, TRMR, and ATY are probably destined to stay on Curve 1 to survive over the near term. As long as most marketers remain the same (not paying attention, not caring, or both), then the Curve 1 market will likely remain really big and lucrative for quite some time. All three of these smaller players are at the bottom of the pack when it comes to delivering returns. Investors need to see more ability to attract ad budget independent of which path management takes. If you can do it on Curve 1, great. If you can cross the chasm on a Curve 2 philosophy, even better.

S4 Capital (aka Media.Monks): From our point of view, the newness of a reimagined holding company is about getting clients to Curve 2 and beyond. A big part of S4’s media positioning (e.g., MightHive acquisition, ~1/3 of revenue) is about helping clients to stand up in-house teams. S4’s programmatic media group has historically been tied at the hip as a reseller of Google’s programmatic stack. Since Google’s demand and supply-side tech can be used to tap profits on Curve 1 or Curve 2, it’s up to S4’s media buyers' ability and disposition to pick their flavor. When competing to win client RFPs (“whoppers”) against bigger media agencies, Curve 2 storytelling, use cases, and quick delivery (better, faster, cheaper) seem like the best place to be when playing a David/Goliath game.

Magnite and Pubmatic: Importantly, the big distinction between Curve 1 and Curve 2 has to do with another fundamental economics concept called “Information Asymmetry.” When only sellers know the quality of the thing they are selling, and buyers have little or no information to assess quality, then buyers tend to overbid (and pay fees along the way). While Curve 1 is defined by Information Asymmetry, Curve 2 is a place of informational balance between seller and buyer. While MGNI and PUBM were born and grew up on Curve 1, we think it’s a matter of when — not if — they shift focus to become Curve 2 suppliers. Similar to S4, as the supply chain continues to tighten SSPs are getting invited into more media buyer RFPs and need a believable quality/scale story to win. The first one there will likely have a nice advantage for a while.

Roku: It’s hard to tell, but Roku’s programmatic business is more likely on Curve 1 and will probably need to stay there for a while (see marginal cost constraints mentioned above). Every time we hear about “CTV, CTV, CTV” as the most-used word in earnings calls, the less we believe the inventory quality is real.

BuzzFeed: Curve 1 feels like home base for BZFD. The stock is off –83% since we added it to our portfolio in December 2021. Assuming adtech investors are betting on a programmatic (and digital ads in general) flight to quality, they might not see BZFD as a company that can get there soon enough.

Taboola and Outbrain: Sure, these two companies might rely on Curve 1 to thrive, but as long as there are starving publishers that buy the clickbait pitch and advertisers that don’t mind that kind of content, then Curve 1 is a great place to be. Similar to BZFD, investors don’t appear to believe in clickbait positioning and have taken the stocks down 75% since this time last year.

DoubleVerify and Integral Ad Science: These two content verification companies create the Ad Quality X-axis. They are responsible for telling buyers what they got for their media money. Was the impression human or bot? Viewable or not? Brand-safe? However, as far as we (or anyone else) can tell, content verification companies are in two kinds of business: 1) the volume maximization business and 2) the insurance business. In other words, they are equally happy to provide a throat to choke (for a price) at Point A or Point C but would likely go out of business at Point B because they’d drown in high margin costs.

Innovid: Innovid is positioned similarly to DV and IAS as a server and monitor of ad quality. Looking at CTV’s cost of revenue sitting at 21% indicates a high marginal cost structure, which usually means a company needs advertisers to spend money on a Curve 1 belief system until their unit economics flip into a positive contribution margin (which might never happen).

Liveramp: Trade-off curves like The Struggle are not only useful to illustrate business model positioning, but also perfect to understand the business models of audience data companies like RAMP and fellow competitors such as Neustar, ID5, InfoSum, and The Trade Desk UID2.0 initiative.

Audience data sits on a trade-off curve where scale trades with data accuracy.

Third-party cookies (3PD) used to be the grease in all programmatic wheels, but all that lubricant has mostly gone away due to regulatory pressure. While 3PD had massive scale, it is/was terribly inaccurate and no better than random targeting.

Field Research: The proof is in the pudding. Check out Nico Neumann’s research on third-party audience data. “The relative average performance of using third-party data according to our sample is worse than random user selection.” (Page 7).

First-party data (1PD) owned by advertisers and publishers is much more accurate, but it lacks scale (e.g., only ~5–30% of users log in to publisher sites, the rest are mostly unknown users that can only be targeted with contextual signals).

The key for data companies like RAMP is figuring out how to get 1PD on new trade-off curves that drive more utility (e.g., accuracy with scale). Until then, Curve 1 is probably the better place to be because data sellers only make money when ad impressions flow. More impressions of any quality are better for revenue than fewer high-quality impressions.

Ask Us Anything (About Programmatic)

If you are confused about something, a bunch of other folks are probably confused about the same exact thing. So here’s a no-judgment way to learn more about the programmatic ad world. Ask us anything about the wide world of programmatic, and we’ll select a few questions to answer in our next newsletter.

Join Our Growing Quo Vadis Community

Was this email forwarded to you? Sign up for our monthly newsletter here.

Get Quo Vadis+

When you join our paid subscription, you get at least one new tool every month that will help you make better decisions about programmatic ad strategy.

Off-the-beaten-path models and analysis of publicly traded programmatic companies.

Frameworks to disentangle supply chain cost into radical transparency.

Practical campaign use cases for rapid testing and learning.