#94: 3Q24 Portfolio Update

Overhauled portfolio; TTD dominates portfolio gains; Landowners vs. Farmers

AdTech Economic Forum NYC 2025 will take place on March 19 at the fabulous New York Times Center. If you’re interested or invested in adtech, it’s the best place to soak in unique content, connections, conversation, and collaboration. ATEF NYC is the Davos of AdTech and invite only so ask for one today.

And if you’re a green shoot adtech company or adtech investor, then check out the AdTech Economic Forum London 2025 on February 6. It’s a pitch event with a twist.

Updated Portfolio

Better late than never, that’s what they say. Our 3Q24 portfolio update is coming a few weeks later than planned. Why? We completely overhauled our equal-dollar portfolio model to get a better and longer historical look at the public adtech space. We also updated our agency portfolio using the same method.

Old Equal-Dollar Portfolio Approach:

The model we’ve been using since Quo Vadis began covered eighteen public adtech companies and incorporated stock prices starting in January 2018. That approach was good enough, but it penalized older public companies like CRTO, MGNI, and TTD that went public in 2013, 2014, and 2016, respectively.

Here’s how it worked: As new players went public during the adtech pandemic craze, our tracking portfolio approach sold the entire portfolio and then re-purchased shares of each company on an equal-dollar basis. For example, if we started with four companies in the portfolio in Year 1, and a fifth one went public in Year 2, we sold all the shares of the original four companies, divided the proceeds by five, re-purchased shares on an equal dollar basis across the five companies and so on as more new companies join the portfolio.

Things have changed: Since launching Quo Vadis in March 2021, two portfolio companies (ADTH and CTV) are no longer public. Cadent acquired Ad Theorent early this year for $324 million (45% premium) and just a few weeks ago MediaOcean acquired Innovid for $500 million (nearly a 100% premium).

And in early November rumors circulated about KKR — the mammoth OG of private equity — taking out IAS. If a Polymarket bet asked — “Will there be at least one more privatization of public adtech in 2025?” — that contract would probably trade at a 99% probability.

Roku could also fall out of our public market portfolio in 2025. Laura Martin from Needham & Co. shared her compelling thoughts last week about Roku getting acquired by the end of 2025.

New Equal-Dollar Portfolio Approach:

Our updated portfolio approach start date begins way back in October 2013 in Criteo went public (See chart below with IPO dates) giving us a longer look-back window and it now includes two companies that we left out of the old approach — Applovin and Perion.

The bigger change is the incorporation of a different equal-dollar method. When a new company enters the portfolio we simply buy $100 worth of shares. At the same time, we also buy $100 worth of the NASDAQ and S&P 500 to compare returns, estimate beta, and examine other valuation metrics across the sector.

Lastly, S4 Capital (aka Monks) used to be included in our original QV AdTech 18 because it owns Mighty Hive (a programmatic business) and the pricing action tended to track with the adtech sector. Since we also included S4 Capital in our agency portfolio, now we are grouping it only with our agency tracker for a cleaner view (more on S4 and the agency world below).

Where do they stand?

With our updated portfolio methodology out of the way, let’s check out our QV16 Big Board.

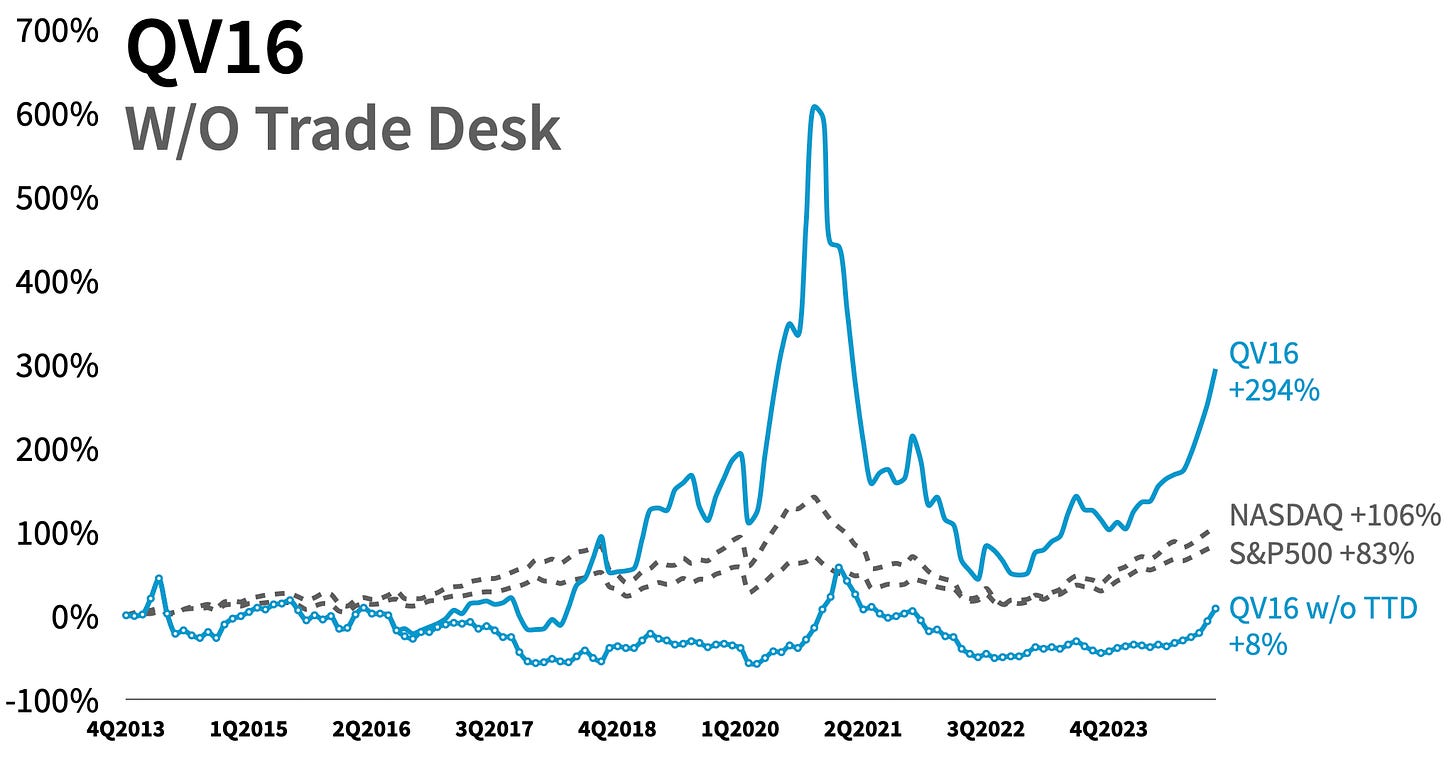

Had you bet $100 in each of the sixteen companies on the day each one went public, you would have $1600 in total funds invested and a 294% gain. In other words, for every $100 invested, you’d be ahead by $294. Compared to the broader market, your $1600 cumulative investment in the NASDAQ and S&P500 would be up 106% and 83%, respectively. Your investment in adtech would have found more than a respectable alpha.

However, only four companies contribute to portfolio gains while the other twelve detract from the gains. It will come as no surprise to our readers that The Trade Desk is the biggest contributor generating 98% of the gains. The other three contributors are Applovin, Zeta (but that could change going forward), and Criteo. Notably, these are the only four companies among the sixteen that are trading above their IPO prices.

Note on Zeta Global: Zeta is involved in a class action lawsuit for violations of §§10(b) and 20(a) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and Rule 10b-5. According to the complaint, the company made false and misleading statements to the market by allegedly creating a scheme using two-way contracts to artificially improve its financial results and utilized round trip transactions to inflate its performance. The claim says the company relied on predatory consent farms to gather user data to drive the majority of the Company's growth. The stock has lost $2.7B in market cap since the news hit the scene.

3Q24 Winners

Looking at year-to-date performance compared to IPO price deltas, Magnite has clawed back 70% of the delta since the beginning of 2024. Nexn International (f/k/a Tremor) has clawed back 41% and Viant has also done well in 2024 clawing back 35%.

FWIW, Buzzfeed has clawed back 12% year-to-date but it also had to sell it’s best asset — First We Feast — for $82.5 million in an all-cash deal. That’s the food and pop culture entertainment brand behind the popular "Hot Ones" YouTube show. The sale was necessary to fund a $100 million short debt payment. Buzzfeed’s market cap is just $135 million. It would not be surprising to see private equity get creative, clean up the balance sheet, bolt on better assets, to turn it around and flip it for a respectable return.

Quo Vadis Quarterly Update is brought to you by Adelaide. Discover why attention metrics should be at the forefront of your digital strategy for better efficiency, ROI, and brand impact. Learn more at Adelaide!

QV16 Trend Lines

One of the benefits of our new approach is gaining a longer historical view going back to when Criteo went public in 2013. Magnite was next in 2014 and then The Trade Desk in 2016. Liveramp became a separate public entity in 2018 and then the adtech IPO market went quiet until the pandemic.

From a stock performance, there was not much excitement going on until 2018 when things started to change. Our portfolio contained just four stocks before the pandemic and was up 193% in February 2020.

When the pandemic happened, the entire market including the adtech sector rose with the tide and took the opportunity to go public. PubMatic kicked things off in 4Q2020 and then eleven others followed in 2021. Most of them except for APP and ZETA are trading below their IPO prices.

It goes to show you. If you think winning and creating free cash flows in Adtech Land is easy it’s not. It is a fiercely fickle and competitive $48 billion global market that is shaping up to become a winner (or a few winners) take-all market that getting relatively smaller. It’s a big fish little pond scenario which is great if you're one of the few big fishes.

For example, if we remove TTD from our portfolio the remaining group would be up just 8% and well below broader market returns.

Agency vs. AdTech + Land Owners vs. Farmers

Similar to the update treatment of our QV16 model, we took the same approach across seven agency groups: IPG, Omnicom, Publicis, WPP, Dentsu, Stagwell, and S4 Capital (Monks). Our QV Agency7 portfolio also starts in October 2013 that way we can compare it to our QV16 portfolio on the same timeline.

Each of the first five agency groups — IPG, Omnicom, Publicis, WPP, and Dentsu — started with a $100 investment in October 2013 and then S4 Capital joined the portfolio with a $100 investment in September 2018 and Stagwell joined in August 2021. Therefore, the total investment across our agency portfolio today is $700.

In nominal terms, our QV Agency7 portfolio is trading at just $725 today (including reinvesting dividends along the way) so it’s returned just 3% since 2013. If take inflation into account of the eleven year perido the real returns would be negative.

Agencies vs. Platforms

When we compare agencies to the two big ad platforms that own most of the ad market — Google and Meta — the case for “your margin is my opportunity” becomes much more pronounced.

Here’s what happened. Let’s first examine this picture through Andy Warhol’s lens and then through a jobs-to-be-done. Andy Warhol famously said:

“In the future everyone will be famous for 15 minutes.” What he forgot to mention was the other side of the coin. “In the future, everyone will have privacy for 15 minutes.”

Life, business, and advertising are full of trade offs. That’s the very essence of economics.

First the Internet happened. Then big data happened And then audience targeting capabilities happened. Perhaps the pace of change was too fast for agencies to keep up and now they (most, not all) are forever caught up in catch-up mode.

Along the way, consumers put the information of their lives online in exchange for more utility (however you want to define “utility”). Trade-offs are everywhere.

From an advertiser’s perspective, they relied on agencies to plan audiences, buy media, and tell them about all the great results (e.g. brand lift, sales, etc.). Then, one day at some point around 2008, both big advertisers and SMB advertisers woke up and asked:

“Do I need a car to get from A to B? No, I just need to get from A to B. In the same vein, they also asked, “Do I need an agency to get the advertising job done? No, I just need to get the advertising job done and the platforms are new best alternative.”

Big ad platforms like Google and Meta (and now Amazon and TikTok too) get advertisers from A to B better than the next best alternative and take what was somebody else’s margin along the way.

That brings us to the economic subject of “Ricardian rent.”

In the early 19th century, economist David Ricardo argued that owners of high quality land would be able to extract a differential gain, or rent, from using higher instead of lower quality land by simply sitting back and letting the farmers bid amongst each other for the higher quality land. Competition would make every farmer's profits identical; the productivity differential, however, would remain and accrue to the holders of higher than marginal quality lands.

With this concept in mind, let’s position agencies and adtech platforms as different types of land owners and clients as farmers. Back in the good old days before the Internet, agencies were gods that cranked out amazing creative assets. Clients were kept super happy and paid a handsome “rent” to farm these creative “lands.”

Back then, buying media was a secondary thing. Creative was everything. Agencies created and owned this high-quality land and effectively rented it to clients who were increasingly willing to pay more rent for better land (better creative driving better sales results).

Things started to change at the turn of the century. The internet was now the new innovation driving total creative destruction. It’s still going on today and the cycles are getting faster (e.g. AI and quantum computing next).

Then an odd thing happened with the rise of marketing procurement. Clients started asking agencies to reduce quality in exchange for lower rent prices. They wanted agencies to be farmers instead of landowners and here we are today.

As digital ads grew and the big platforms got bigger (which now include Amazon, TikTok, and The Trade Desk to some extent), agencies became farmers. Meanwhile, the platforms created increasingly more productive land aided by a key nutrient — data — and became the new landowners.

From the get-go, these new landowners realized something agencies either missed or were too slow, or were too bogged down in a Kodak moment. Data has a very interesting characteristic called “increasing marginal returns” such that one data asset joined with another data asset has exponential value. You can think of this similar to Metcalfe's Law about network effects where the value of data is equal to the square of each unique data set.

Anyhow, most goods have decreasing marginal returns. For instance, one umbrella is good when it is raining outside. You can carry a second umbrella in case the first one breaks. If you carry around a third and then a fourth umbrella you end up with decreasing marginal returns. Data has the opposite characteristics. That’s why it’s so valuable. That’s why Google and Meta can create such insane cash flows.

In summary, data is the primary nutrient of high-quality advertising land. Data owners exist to extract a differential gain, or rent, from providing higher-quality data. They can simply sit back and let the farmers (advertisers and agencies) bid amongst each other for higher-quality data and the competition amongst these farmers makes every farmer's profits diminished and identical. The productivity differential, however, accrues to the holders of the high-quality land (data). Hence the trend chart above is captioned as “Walled Garden Business Models Rule.”

Omnicom Acquires IPG, but Publicis has become a landowner

The last few months have been filled with a steady stream of M&A, but nothing compares to the mega-merger of Omnicom and IPG. The most obvious positive aspect folks are talking about is cost synergies perhaps in anticipation of continuous cost reduction pressure from procurement. But ultimately the big outcome of such a complicated merger should be about “OmniPublic” shifting from being a farmer to a data landowner like Publicis has accomplished.

If you go back to the peak of the pandemic boom in 4Q21 and look at agency stock performance going forward you’ll see that “Publicis One” and CEO Arthur Sadoun have separated themselves from competitors albeit with OMC in second place. Given WPP’s uphill battle to find its place in the current world, it’s not unrealistic to imagine Publicis initiating a merger with WPP to achieve the same cost synergies and more importantly, put WPP assets and talent under proven leadership that knows how to morph from a farmer to a landowner and maximize shareholder returns.

A Wrod on S4 Capital: Revenue productivity is the name of the game

S4 Capital is trading at about 20% above its 52-week low. While that is not where any company wants to be given robust broader market returns, the future is bright if one thing changes and it’s all for the taking with management discipline and refined incentives. It’s the same story for every adtech company — public or private, big or small, new or old.

The main driver of value creation can be traced back to revenue per employee.

S4’s revenue productivity is $152K per employee (based on 1H24 numbers).

Cost of revenue was 12% of revenue

Staff cost was 84% of revenue and 80% of total operating expenses leaving just a 4% operating profit margin.

Invested capital as of 1H24 was $1.56 billion

Assuming 25% cash taxes, the return on invested capital (ROIC) today is around 2% which is why the stock is trading so low.

As AI implementation materializes (if managed well) and with just a few nice client wins, the goal should be to grow revenue productivity to ~$225K, for example, by the end of 2026. That’s the only true worth that should matter for management. Every day, week, month, and quarter that bar chart is either moving up and to the right or not. All performance/incentive plans should be tied to that bar chart.

Since invested capital should grow around half as much as revenue growth, invested capital in 2026 will be around $1.9 billion resulting in a ~22% ROIC which translates to at ~$200 million+ in free cash flow.

If there is one thing that will move a stock price it’s the spread of ROIC over the cost of capital. That’s what cash flow machines do. And over the long run, that’s the only thing investors care about.

Every adtech company and every agency has a huge opportunity. It’s never going to be easy. What’s the plan to get there? Set high aspirations (e.g. 30% ROIC). Get quick and easy wins. Constantly communicate signs of momentum. Sustain the impact (e.g. when you’re done the machine can run on its own).

Disclaimer: This post, and any other post from Quo Vadis, should not be considered investment advice. This content is for informational purposes only. You should not construe this information, or any other material from Quo Vadis, as investment, financial, or any other form of advice.