“We are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars.”

Leave it to Oscar Wilde to sum up the adtech world. Rishad Tobaccowala might add a twist as he did at AdTech Economic Forum NYC a few weeks ago:

“And some of us wear perfume.”

That metaphor also sums up the fundamental essence of the open web programmatic demand curve. Let’s get into it.

Won't you take me to Funkytown?

Let’s first take a walk down memory lane to when programmatic advertising started to take off and why marketing procurement got into the game. Quo Vadis likes to keep it fun, so get into the mood with the 1980 classic “Funky Town” by Lipps Inc.

If marketing procurement folks had a programmatic theme song, Funky Town would have to be it. They started dancing to the programmatic beat around 2008/09 just after the Great Recession.

Before the Great Recession, marketing procurement had already gained a lot of power within the marketing organizations of big brands. Their job was (and still is) to reduce advertising costs, meaning they look at prices before value and usually confuse them as being the same. At least that’s what observation suggests they do day in and day out. Their conflation is critical for the programmatic demand curve to thrive.

Price-Value Conflation Example:

A current vendor costs $100/year and handles $1,000 in media budget for an advertiser. Procurement sees a 10% fee. The vendor produces really good outcomes worth $10,000 to the client.

Procurement thinks (or is told) that 10% is too much. So they put the vendor into review, hire a consultant to run the process and end up picking a new vendor costing $50 or 5%. The new vendor delivers outcomes worth $5,000.

The company saves $50 and loses $5,000 not including the cost of transitioning from one vendor to the other nor the cost of losing the institutional knowledge of all the marketing people who leave the business because working for procurement is too irritating.

Moral of the story: Stepping over dollars to pick up pennies is never a good investment choice. When things were good

Before 1995 (more or less), media agency fees were ~15%. That fee covered media buying and a steady of creative ideas. Clients paid 15% on media spending and also covered creative production pass-thru costs. Everyone was happy and the creative output was very good.

With the growth of cable TV over the previous 15 years, CPMs were on the rise. Agencies were benefiting from 15% fees on rising prices which translated into juicy revenue growth, fancy agency office spaces, wining and dining, and all the accouterments that go along with a rising tide. Life was good.

Digital workloads grow

After 1995 when websites and digital ads sprang up, agency revenues grew even more. It was an exciting time.

Similar to the AI craze that we’re all experiencing in the current cycle, back then the chatter and fear was about how the Internet was going to take away jobs. It certainly changed the jobs people do across every industry, but for the advertising world it created a mountain of new work that needed to get done.

When the 2001 post-dot.com boom recession came calling, marketing procurement came more into play. They thought agencies were living too large, so they put them into review cycles and tended to select the one that offered the lowest price.

The Great Recession

By the time the Great Recession happened in 2008/09, fees had moved from 15% to 10% or lower. Since shit tends to roll downhill, agencies were forced to lower their costs if they wanted to generate the same net income as before and payout an expected dividend to shareholders (~50% payout ratio and ~5% dividend yield).

So what did agencies do? They offshored talent to lower-cost countries, juniorized talent in home markets, and exchanged title inflation for salary increases amongst other ways to cut corners and still deliver service to clients who didn’t seem to care much about the increase in digital workloads.

Going for broke

As Winston Churchill said,

"Never let a good crisis go to waste."

The Great Recession presented a massive opportunity for procurement to get agencies to reduce fees even more, this time down to ~5% and even lower in some cases.

At the same time, workloads for staffers kept growing. Imagine a big brand like P&G in 2008 spending roughly $5 billion on media across $8.6 billion in total worldwide ad spend (television, print, radio, internet, promotions, and creative production, see 2008 10K).

Imagine, 10% fees on $5 billion in media spending is $500 million in media spending on a single account. Assuming $35/hour per your average agency staffer ($70K per year ranging for senior to junior staffers), P&G funded roughly 7,000 agency people worldwide. With 138,000 employees at the time, P&G effectively outsourced 5% of its workforce to agencies.

When fees were reduced to say 3% after the Great Recession, P&G’s agencies could only staff around 2,100 people at the labor cost as before. So, even if they reduced labor costs by 50% through the aforementioned cost-reduction strategies, they would still only be able to staff 4,200 people to take on more workload than before.

Magic happened, programmatic saves the day

With increasing workloads, procurement seemed to forget about the fact that the show must go on. The work never stopped and someone had to get it done.

At the time, programmatic advertising was still crossing the chasm but everyone knew it was the future. Anytime a brand leader heard about the magic of 1-to-1 audience targeting they saw visions of the holy grail dancing in the air like a Monty Python animated dreamscape. A new golden age of advertising was emerging.

The idea of programmatic media buying was mesmerizing. Programmatic had the power to make the marketer’s dreams come true on the back of what everyone called “remnant” or “unsold” ad open web inventory.

Media agencies, which were now governed by giant consolidated holding companies, were the first to see the light. It materialized in the form of giant programmatic trading margins.

That’s precisely when the foundations of the programmatic demand curve took root. The more that agencies could get marketers to allocate media budget to low-priced programmatic inventory, the more fees the agency made. From a business model perspective, agencies saw an opportunity to average their way back to 15% effective fees.

Starting around 2010, the demand-supply flywheel hit overdrive creating a win-win-win bringing marketers, procurement, and agencies into balance. The machinery of invested capital was well formed by then with Google buying Doubleclick ($3.1 billion) and Admob ($750 million), Yahoo buying Right Media ($680 million), and GroupM buying 24/7 Real Media ($649 million).

Winner 1: Procurement was more than happy to maximize media budget allocation to $1.00 CPMs, aka “cheap reach” ad inventory. The more they allocated, the more they could claim, “We lowered our average CPMs by 10% this year.” That’s precisely the kind of win procurement is incentivized to get.

Winner 2: Agencies were equally happy with the new gravy train which funded staffers and supported dividend payouts to shareholders. As Brian Lesser correctly and famously said a few years later at Cannes Lions, “We’re [Nexis, f/k/a "Xaxis] transparent about not being transparent.” The most honest words ever spoken in Programmic Land.

Winner 3: The CMO’s organization was also happy because they were delivering the holy grail and indirectly funding the agency staffers they worked with every day vis-a-vis high programmatic fees. That’s a nice win too.

Once the flywheel started turning, it was full speed ahead

As the years went by, procurement could ratchet up more media budget allocation toward $1.00 CPMs and keep reporting more CPM reductions in their annual reviews. Since nobody was looking (or incentivized to look) or cared about inventory quality (e.g. human vs non-human users mixed with ad placements), the win-win-win created a natural incentive for adtech suppliers to fill the market’s need with an endless supply of low-quality inventory.

Quo Vadis likes to remind readers that where there is demand, someone will be willing to supply it. You might not like it, but that’s how our human self-interest works.

Self-interest behavior is not new. In Adam Smith’s seminal 1776 work, The Wealth of Nations, he argued that individuals pursuing their own self-interest unintentionally contribute to the overall good of society, hence the metaphor of the "invisible hand."

"It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest."

The irony of timing and the collapse of collateralized debt obligations

Ironically, the Great Recession was caused by a lemon market made of collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) that ended up crashing. And out the other side came a new lemon market called programmatic. It’s the stuff of great movies!

When the big banks wrapped up sub-prime mortgages into endless versions of CDOs (e.g. curated deal IDs?) and rating agencies like S&P, Moody’s and Fitch (aka adtech verification vendors and industry standards committees) gave these bonds A+ ratings, the greatest lemon market ever was created and it eventually imploded in grandiose style.

Nobody bothered to look under the hood because too much money was being made. Here’s the opening scene from The Big Short to refresh your memory.

INT. SOLOMON BROTHERS - CONFERENCE ROOM - 1979 - DAY 2 Lewis and HIS TEAM are doing a presentation to a bunch of STATE PENSION FUND MANAGERS with an old-fashioned OVER HEAD PROJECTOR.

Asymmetric game matrix

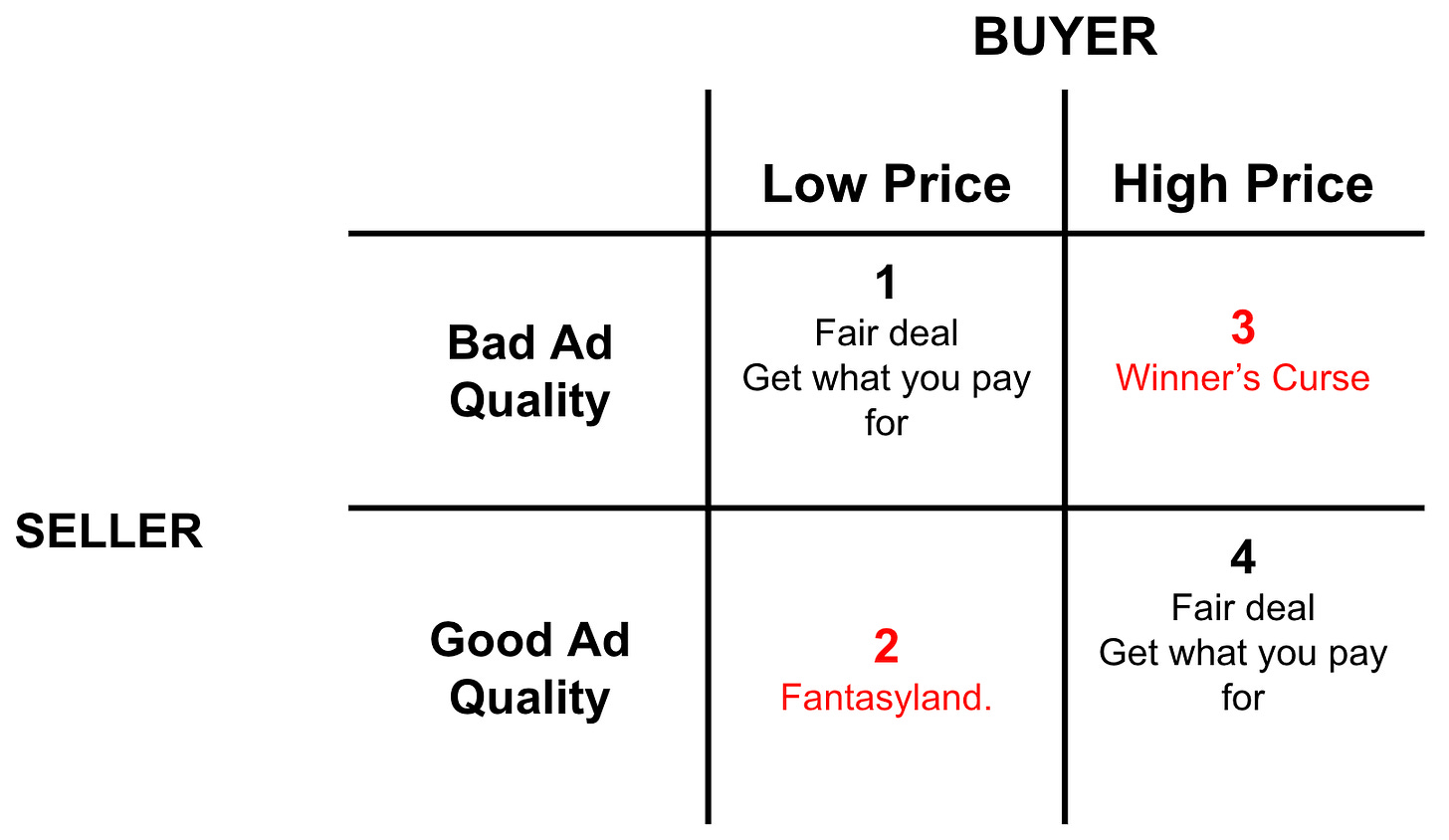

The programmatic flywheel of demand and supply is a similar story. We can illustrate it as a 2 x 2 game between a buyer paying a high or low price for ad inventory and a seller who supplies good quality or bad quality.

The market starts when a seller promises the best ad quality at the lowest price (on a repeatable always-on basis) as if that kind of inventory is in infinite supply. If the buyer is mesmerized and/or incentivized enough to believe it, and if the rating agencies keep verifying the veracity of the ad quality, then Box #2 becomes a massive market attracting all kinds of self-interested supply chain providers. Good for them — the world needs ditch diggers too and ditch diggers need shovels.

If the ad quality turns about to be bad, then the buyer gets what he/she pays for and should be fine with the outcomes or lack thereof. The worst-case scenario is known as winner’s curse. That’s when a buyer overpays to win an auction only to find out after the fact he/she bought junk.

What do you expect from $1.00 CPMs? Let’s do some quick math to illustrate the foundations of programmatic demand.

Imagine you call the shots for P&G marketing procurement and you allocate your media budget as follows:

25% Linear TV, $50 CPM

5% OOH/Radio/Print, $25 CPM

5% CTV, $20 CPM

15% YouTube, $20 CPM

15% Search, $5 CPM

25% Social, $10 CPM

5% Retail Media, $7 CPM

5% Open Web Direct Guaranteed, $20 CPM

You have a 75% allocation to digital and 25% to tradition which feels about right. Your weighted average CPM across the board is $22. You have not yet allocated any budget to open web programmatic but you’re about to jump in.

The next day, you go head over heels into the programmatic game and decide to reallocate your mix and artificially reduce your weighted average CPM. You shave off a bit here and there to find 15% that now goes to open web programmatic at $1.00 CPMs. Voila… now you can report a 17% reduction in CPMs. You’re going to crush your next annual review.

The next thing you know, a press release goes out and AdWeek, AdExchanger, Digitday, and WSJ CMO Today run the headline, “P&G reduces costs by 17%.”

P&G’s shareholders love the news. Their agency roster and all their programmatic partners are popping champagne like it’s Studio 54 and dancing to Funky Town. Consumers don’t know the difference because the ads are not reaching them anyway, but the bots, non-viewable placements, and MFA are eating it up.

Along the way, P&G gets a free ride not having to pay the negative externality and hidden cost of waste in the form of Co2 emissions from all the programmatic factory data crunching.

And that’s why marketing procurement is the pillar of the programmatic demand curve.

Auction pricing and outcomes

By 2025 the procurement-led adtech flywheel has grown into a giant $69 billion global programmatic market with vested interests all over the place. Investors have funded many billions of invested capital into hundreds of companies across a sprawling interconnected supply chain.

Up until now, marketers and procurement did not have to think or worry much about the basics of auction pricing and outcomes. At least that’s what observation suggests because actions speak louder than words said on stages at Cannes Lions.

There are positive outliers like Shenan Reed, Global Media Office at General Motors. Here’s what she said on stage with Bob Lord at Scope3’s Landscape event a few weeks ago:

“We are on this downward spiral… I need CPMs to be 5% less this year, 5% next year [and so on]:”

As the programmatic demand curve is constructed to from the beginning to today, it was simply easier for marketers to have confidence in the intent of all the adtech counterparties they deal with (the very definition of trust) and easier to believe that they were getting an incredible bargain every time they won an auction.

Let’s translate that belief system into two stacked bell curves with an average and a standard deviation. The top bell curve expresses prices paid for impressions and the bottom one is ad quality.

For the most part, buyers have access to observable pricing data from their DSP and other partners. The price curve has a distribution of some form with an average price and standard deviation.

Buyers also have an ad quality distribution curve with an average ad quality and standard deviation, but this data has gone mostly unobservable. The more observable true ad quality becomes, the more the adtech players will be impacted by creative destruction that will likely reshape how industry earnings are shared and who gets them.

Starting around 2008 until now, the growth of open web programmatic has been driven by buyers paying a high positive standard deviation price in exchange for negative standard deviation ad quality. That’s winner’s curse — you win the auction but overpay for what you get.

And just like Lewis Ranieri’s mortgage-backed security in The Big Short, as long as adtech did not shine a light on the misalignment between price and quality while marketing procurement was hooked on allocating more ad budget to the lowest prices (instead of seeking value-based outcomes), the adtech market kept growing.

Put another way, let’s say you buy a mix of Linear TV, OOH/Radio/Print, Premium Brand CTV, YouTube, Search, Social, Retail Media, and Open Web Direct Guaranteed on top brand publishers for a $20 average CPM. You rank these mediums at the high end of your quality scale. If you then buy $1.00 CPM programmatic inventory as the next “least-worse” alternative, then you are implying a waste or “junk inventory threshold” of 95%.

For example, if only 5% of your programmatic buy is what you’d consider passable advertising inventory (ask your creative people, they have a good eye), then your effective CPM on $1.00 is $20 which is equal to the average price you pay for those high-quality allocations.

Back to our P&G example

In 2024, P&G expensed $9.6 billion on total ad spending (media, creative, and promotions, excluding trade marketing expenses).

Let’s assume 60% goes to media and the rest to creative, promotions, and other related ad expenses which translates to $5.8 million in media spending.

Assume 10% goes to open web programmatic or $580 million. The other 90% goes to the higher-quality mediums discussed above at a $20 average CPM. That means P&G bought 260 billion impressions on high-quality mediums in 2024. All roads always lead back to reach and frequency trade-off curve for big brand advertisers.

Assuming a global target population of 6.5 billion (e.g. cut off the tails for very young people and very old people who probably don’t care much about ads). That means in 2024 P&G delivered 40 ads per target consumer.

Now let’s say P&G allocates the last 10% of its media budget to open web programmatic at $1.00 CPMs which buys an “incremental” 576 billion impressions or more than 2x what they bought with the other 90% of the funds. But only 5% of it buys high enough quality impressions which means just four extra impressions reach each target consumer.

Juxtaposing the adtech sales pitch

Imagine if P&G could somehow only buy the 5% good stuff by aligning their standard deviation of price and quality. If they achieved what should be totally doable then they could return $511 million to shareholders which would be an outstanding 13% dividend yield!

Our line of thinking begs the question: If all the data crunching, platform sophistication, and AI prowess of the adtech sales pitch is true, then how hard could it be to snuff out 95% of the junk and only buy 5% of the good stuff?

What if?

"Every act of creation is first an act of destruction." — Picasso

As adtech stands today, profound changes are shaking the foundations of the demand curve. If demand moves from a total misalignment of price and quality to total alignment, then the entire market will change. Some winners will prevail and others will not make it out alive.

Quo Vadis thinks a few well-positioned adtech players will not only lead the way but might also create the change causing a new comparative paradigm to emerge forcing what used to be competitors to exit the market.

Venture capital portfolios holding misaligned adtech vintages from the previous innovation cycle will look to sell what might be good underlying technology assets running obsolete business models. There will be exits, but valuation multiples will be lower than desired with downward pressure through 2025 and 2026. Whatever buy-side M&A is willing to pay for older vintage adtech today will be lower tomorrow.

New venture funds will happily support the next adtech innovation cycle betting that price-quality alignment is the foundation of the new demand curve.

Younger adtech companies founded and funded over the past few years could see nice exits sooner than founders and venture funds are used to with the past vintage.

The one thing we all know for sure: It’s going to be more fun than ever before because the next great adtech company isn’t just disrupting the market, it’s erasing it and drawing a new demand curve.

Disclaimer: This post, and any other post from Quo Vadis, should not be considered investment advice. This content is for informational purposes only. You should not construe this information, or any other material from Quo Vadis, as investment, financial, or any other form of advice.